“The Martyr Who Died for Us All”

Written by: Kelly Durham

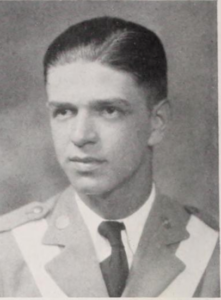

Of the nearly five hundred names listed on Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor, none has been more widely reported than  Rudolf Anderson, Jr. Anderson, a 1948 graduate in textile management, was the sole casualty in the Cuban Missile Crisis which pushed the United States and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war sixty years ago this week.

Rudolf Anderson, Jr. Anderson, a 1948 graduate in textile management, was the sole casualty in the Cuban Missile Crisis which pushed the United States and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war sixty years ago this week.

Rudy Anderson grew up in Greenville and showed an interest in flying even as a toddler. When bad weather forced an airplane to make an emergency landing near the Anderson’s home, the family took in the pilot for the night. The next morning, the flyer took three-year-old Rudy to see his plane, delighting the child. Throughout his early childhood, Rudy built model airplanes. He even attempted to fly himself, leaping from a window—and ending up in the hospital with a broken arm. It wouldn’t be his last wingless flight—or his last crash landing.

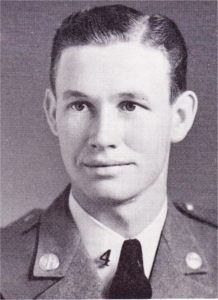

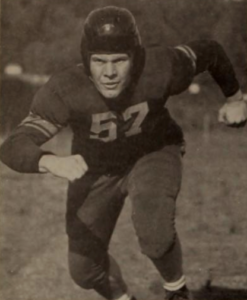

Rudy was a member of Buncombe Street Methodist Church and was an Eagle Scout. He served as manager on Greenville High School’s 1943 state championship football team. Rudy graduated from Greenville High School in 1944 and enrolled at Clemson College.

At Clemson, Rudy earned academic honors and participated in intramural sports. As a cadet, he was a member of the Executive Sergeants Club, and the Senior Platoon, composed of the most precise senior cadets. The Senior Platoon drilled each morning and evening and highlighted the annual Mothers’ Day parade on campus. It also marched at halftime during Clemson football games. Anderson was among the first Clemson cadets to participate in the newly-formed Air Force ROTC program, attending summer training at Keesler Field, Mississippi.

Just three months short of graduation, Rudy embarked on another wingless flight. According to The Tiger, Rudy was attempting to catch a pigeon that had flown into the second barracks. Rudy chased the bird down the third floor hallway and was unable to stop when it flew out the window. Rudy went out the window as well, bouncing off the eaves over the entrance of the barracks, breaking his fall, and saving him from more serious injuries. Despite a fractured pelvis, Anderson recovered quickly and graduated on schedule.

Anderson received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Air Force, but he was not ordered to active duty as the military was still declining in size from its World War II peak. Instead, Anderson took a job with Hudson Mill in Greenville.

Anderson was building a career in textiles when, in June 1951, he was called into the Air Force. The Korean War was escalating and the United States was determined to hold the line there against Communist aggression. Anderson was assigned to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida for nine months. Before departing for his next assignment, Rudy met Jane Corbett with whom he would correspond over the next three years as his Air Force career carried him halfway around the world. In August 1952, Anderson began flight training at San Marcos, Texas. He was selected for single engine jet training and sent to Webb Air  Force Base in Texas where he earned his wings in February 1953. He was next sent to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada where he learned to fly the F-86 Sabre, the Air Force’s primary air combat fighter of the Korean War.

Force Base in Texas where he earned his wings in February 1953. He was next sent to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada where he learned to fly the F-86 Sabre, the Air Force’s primary air combat fighter of the Korean War.

In July 1953, the Korean War ended in a truce, but the need for intelligence on both Chinese and Soviet intentions in the region drove the United States to conduct reconnaissance flights. Anderson was assigned to the 15th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron at Kunsan Air Base in South Korea. Flying specially-equipped RF-86 jets, Anderson and his comrades flew over Chinese and Soviet territory at high altitudes, their weapons replaced with cameras. In nearly two years in Korea, Anderson was twice awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

On a trip home before his next duty assignment, Anderson proposed to Jane Corbett and they were married in November 1955 near Larson Air Force Base in Oregon. Rudy’s prowess as a reconnaissance pilot was well-known and, following attendance at an Air Force school, he soon found himself back in Nevada at desolate Groom Lake, a dry lakebed known as “The Ranch.” Here, Anderson would learn to fly the secret U-2, an unarmed, very high altitude reconnaissance aircraft developed by the CIA.

In March 1957, Jane gave birth to Rudolf Anderson, III. He would be followed by a brother, James, two years later. Anderson meanwhile was flying operational missions in the U-2 as a pilot in the 4080th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing headquartered at Laughlin Air Force Base, Texas. By 1962, Major Anderson and his colleague Major Richard Heyser were considered the Air Force’s most accomplished U-2 pilots.

Overflights of areas of interest were nothing new. Anderson had flown over the territory of other nations while in Korea. The United States had famously lost a U-2 over the Soviet Union in 1960. That aircraft had been downed by surface-to-air missiles, its pilot captured and put on trial. U-2s had provided aerial photographic intelligence from Cuba before the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion. So, when temperatures began to heat up over the possible installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba in the fall of 1962, it was only natural that Anderson, Heyser and the other U-2 pilots of the 4080th would be called upon.

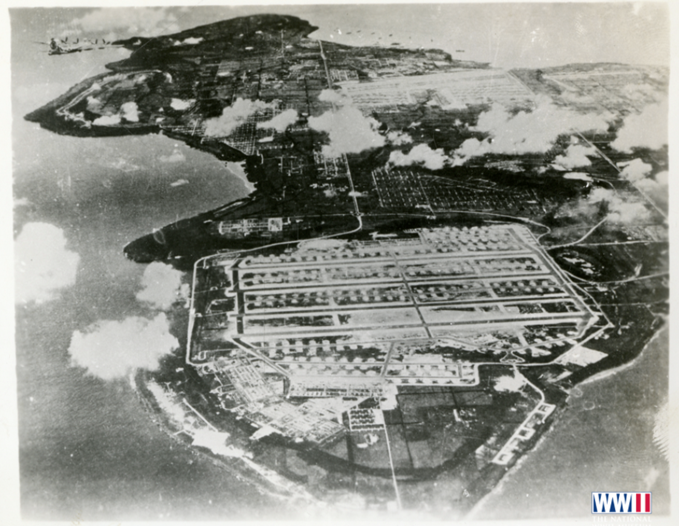

U-2 flights over Cuba in the late summer had noted disturbing build-ups of Soviet installations and equipment. The Kennedy administration was torn between the need for more frequent reconnaissance flights and the fear that such flights would provoke a response from the Cubans—or worse from the Soviets. Nonetheless, periodic overflights continued. Then, on October 14, Major Heyser brought back disturbing images.

CIA photo interpreters identified Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles being installed near San Cristobal, Cuba. In addition, Soviet surface-to-air missile defenses were being set up, though neither weapons system was as yet operational. These discoveries triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis—and would cost Rudy Anderson’s life.

CIA photo interpreters identified Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles being installed near San Cristobal, Cuba. In addition, Soviet surface-to-air missile defenses were being set up, though neither weapons system was as yet operational. These discoveries triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis—and would cost Rudy Anderson’s life.

Over the following thirteen days, the United States increased the number of U-2 reconnaissance flights over Cuba despite a prediction from a CIA analyst that there was a one-in-six chance of losing an aircraft. Anderson and Heyser flew again on October 15. On October 17, six U-2s flew the length of Cuba from west to east ensuring nearly complete photographic coverage of the island. Beginning on the 18th, Anderson’s routine was to fly every other day, but the weather soon disrupted this schedule. Anderson encountered poor visibility due to cloud cover on October 23. The approach of Hurricane Ella cancelled missions scheduled for the 24th and 26th and only one mission was flown on October 25.

The October 25 mission, flown by Captain Gerald McIlmoyle, coincided with the high drama of a diplomatic showdown at the United Nations. US Ambassador Adlai Stevenson and Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin engaged in a heated debate. After repeated Soviet denials of the presence of offensive weapons in Cuba, Stevenson shared the incriminating photos taken by the U-2 pilots. As Stevenson and Zorin fought with words and pictures, McIlmoyle was battling for survival.

McIlmoyle was nearing the end of his mission, much of which had been obscured by clouds. As he passed over a surface-to-air missile site near Banes, the weather cleared. Suddenly, McIlmoyle’s yellow radar warning light illuminated, alerting him that his aircraft was being pinged by enemy radar. As McIlmoyle turned his aircraft, he spotted the contrails of two missiles streaking toward him. He maneuvered to avoid the missiles and saw them explode about a mile away. At this point, he was already on his outbound leg and so he continued on to his base in Florida where he landed and reported his encounter. McIlmoyle claimed that when he landed, an Air Force general met him at his aircraft and told him that he had not been fired on and that he was not to report the missile attack. McIlmoyle, who would reach the rank of brigadier general, disregarded the order and told his fellow pilots of the attack.

On October 27, with the world edging toward nuclear disaster and leaders in Washington and Moscow pondering their next steps, Rudy Anderson prepared for his final flight. Four flights had been planned for the day, but the weather was again poor. Three of the flights were cancelled, but Anderson elected to go forward with his mission because so much of McIlmoyle’s coverage had been obscured by clouds and the need for fresh intelligence was critical.

Anderson awoke early, ate a high protein breakfast, and donned his pressure suit. Two hours before his scheduled takeoff time, he began breathing pure oxygen. Anderson climbed into the U-2’s narrow cockpit and with the help of his check pilot, completed a series of checklists. He shook hands with his check pilot, and gave a thumbs up as the canopy was closed. At 9:09 a.m., Anderson’s U-2 streaked down the runway of McCoy Air Force Base and climbed into the Florida sky.

Anderson leveled off at 72,000 feet and headed toward Cuba on what would be his sixth mission of the Crisis. But on this day, there was a new factor in play that had not been present on his previous missions. The night before, Cuban leader Fidel Castro had ordered the island’s air defenses to fully operational status. Castro expected an American invasion, to include tactical aircraft, and he had placed his defense forces on alert. Soviet officers manning the SA-2 air defense missiles were tracking Anderson’s flight on radar and growing more concerned as he got closer to the medium-range missile sites they were guarding.

Soviet General S. N. Grechko was commanding the surface-to-air missiles. As Anderson turned over Guantanamo Bay to begin a westward track over Cuba, Grechko feared the U-2 was completing its mission and preparing to return to Florida with potentially damning intelligence photographs. After repeated requests for guidance from Soviet leadership resulted in no response, and with Castro’s orders no doubt on his mind, Grechko decided to take action. He ordered the 1st Battalion of the 507th Anti-Aircraft Rocket Regiment at Banes to fire.

At 1019, two SA-2 missiles roared off their launch rails and streaked skyward. Shrapnel from at least one of the exploding missiles pierced the cockpit of Anderson’s U-2 and punctured his pressure suit. The resulting instant loss of pressure at that high altitude killed Anderson immediately. The aircraft began a long spiral to the ground, crashing near the missile battery that had brought it down.

When the news reached the White House, the president’s brother Robert Kennedy would later write, “the whole course of

Soviet soldiers examine the wreckage of Major Anderson’s U-2.

events” changed. There was a feeling “that the bridges to escape [the Crisis] were crumbling.”

But instead of resulting in additional escalation, the death of Major Anderson had a sobering effect. Even the bellicose Soviet leader Khruschev recognized that without immediate action the Crisis would spin out of control. Khruschev’s son, Sergei, recalled that Anderson’s death was “the very moment—not before or after—that father felt the situation was slipping out of his control.”

This critical moment compelled the Americans and Soviets to reach an agreement to resolve the Crisis. The Soviets agreed to remove their offensive missiles from Cuba in exchange for a pledge from President Kennedy not to invade the island. In addition, Kennedy privately agreed to a later withdrawal of American missiles from Turkey.

Rudolf Anderson’s sacrifice, just as the Crisis appeared headed toward disaster, provided the sobering impulse to find a compromise. His death likely saved millions of lives. CBS News commentator Eric Sevareid described Anderson as “the martyr who died for us all.”

Rudolf Anderson was survived by his wife Jane, sons Rudolf III age 5 and James age 3. A daughter, Robyn, was born seven months after his death. At the direction of President Kennedy, Anderson was awarded the first Air Force Cross.

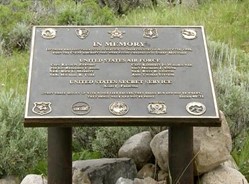

Following the Crisis, Anderson’s remains were returned to the United States. He is buried at Woodlawn Memorial Park in Greenville. A memorial to Major Anderson was established in Greenville’s Cleveland Park.

For additional information about Major Rudolf Anderson, Jr. see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/rudolf-rudy-anderson-jr/

For more information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/

See also:

Alone, Unarmed, and Unafraid Over Cuba: The Story of Major Rudy Anderson, by Major Geoffrey Cameron, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, 2017, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1039301.pdf.

Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis, by Robert F. Kennedy, W. W. Norton & Co., New York, 1969.

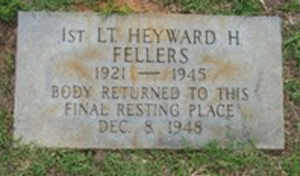

One month after graduation, Second Lieutenant Fellers reported for duty at Camp Wolters, Texas, the largest infantry replacement training center in the country. After a stint at Fort Meade, Maryland, Fellers shipped overseas in August 1944.

One month after graduation, Second Lieutenant Fellers reported for duty at Camp Wolters, Texas, the largest infantry replacement training center in the country. After a stint at Fort Meade, Maryland, Fellers shipped overseas in August 1944.

The Ventura was normally crewed by six men, but on this flight, with no operational mission en route, Staff Sergeant Lawhon and the two pilots, Second Lieutenant Joe Hanna and First Lieutenant Robert Smith, were the only official crew members. Three other service men were listed on the flight manifest as passengers. The aircraft departed Red Bluff at 1300 hours on a flight plan to Medford. With pilot Hanna at the controls, the Ventura penetrated a light overcast soon after departure and continued to climb through layers of clouds. In the vicinity of Redding, California, the weather closed in and Hanna switched to instrument flying. At this point, extreme icing conditions were encountered.

The Ventura was normally crewed by six men, but on this flight, with no operational mission en route, Staff Sergeant Lawhon and the two pilots, Second Lieutenant Joe Hanna and First Lieutenant Robert Smith, were the only official crew members. Three other service men were listed on the flight manifest as passengers. The aircraft departed Red Bluff at 1300 hours on a flight plan to Medford. With pilot Hanna at the controls, the Ventura penetrated a light overcast soon after departure and continued to climb through layers of clouds. In the vicinity of Redding, California, the weather closed in and Hanna switched to instrument flying. At this point, extreme icing conditions were encountered.

northern South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese were seeking to disrupt a vital supply link between the sea and the Marine Corps’ Dong Ha combat base in preparation for their upcoming surprise Tet Offensive.

northern South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese were seeking to disrupt a vital supply link between the sea and the Marine Corps’ Dong Ha combat base in preparation for their upcoming surprise Tet Offensive. Medal.

Medal.

Hubbard was soon ordered back to Nebraska where he received additional training in combat flying in preparation for deployment to Europe. In December 1944, Hubbard arrived in England as a pilot assigned to the 388th Bomb Squadron, an 8th Air Force unit stationed at Snetterton Heath in the southeastern part of the country.

Hubbard was soon ordered back to Nebraska where he received additional training in combat flying in preparation for deployment to Europe. In December 1944, Hubbard arrived in England as a pilot assigned to the 388th Bomb Squadron, an 8th Air Force unit stationed at Snetterton Heath in the southeastern part of the country. accidents, including eight takeoff accidents. Mercifully, not all of them were fatal.

accidents, including eight takeoff accidents. Mercifully, not all of them were fatal.

300,000 Americans who died from the Spanish Flu between September 1918 and January 1919.

300,000 Americans who died from the Spanish Flu between September 1918 and January 1919.

Zeigler’s classmates observed his “individuality, sincerity, and fineness of purpose” and elected him as president of the Class of 1923, an august group that included a future governor and US senator as well as a world famous journalist and author. Taps wrote that Zeigler had “been recognized as a leader among us, and has tackled every problem set before him in his quiet honest way.”

Zeigler’s classmates observed his “individuality, sincerity, and fineness of purpose” and elected him as president of the Class of 1923, an august group that included a future governor and US senator as well as a world famous journalist and author. Taps wrote that Zeigler had “been recognized as a leader among us, and has tackled every problem set before him in his quiet honest way.” manager of the depot’s aircraft repair shop. At approximately 1550 hours, Zeigler took off to the west. Upon reaching an altitude of twenty to thirty feet, the aircraft leveled off and then nosed down into a flat dive, striking a road about 150 feet from the end of the runway. The impact sheared off the landing gear and the faring of the right engine’s nacelle. The A-20 bounced into the air and appeared to continue straight ahead while climbing to about 200 feet. Zeigler attempted to make a wide turn to the left to return to the field, but witnesses reported that the airplane was flying in an “extremely tail low position and gradually losing altitude.” Faced with a deteriorating situation, Zeigler elected to land in a small field about two miles southwest of the runway. The plane hit the ground on its belly, the force of the impact flipping it onto its back and causing “total damage.” Both Zeigler and Copeland were seriously injured. Copeland died four days later on Sunday, December 6. Zeigler passed away the following Wednesday, December 9.

manager of the depot’s aircraft repair shop. At approximately 1550 hours, Zeigler took off to the west. Upon reaching an altitude of twenty to thirty feet, the aircraft leveled off and then nosed down into a flat dive, striking a road about 150 feet from the end of the runway. The impact sheared off the landing gear and the faring of the right engine’s nacelle. The A-20 bounced into the air and appeared to continue straight ahead while climbing to about 200 feet. Zeigler attempted to make a wide turn to the left to return to the field, but witnesses reported that the airplane was flying in an “extremely tail low position and gradually losing altitude.” Faced with a deteriorating situation, Zeigler elected to land in a small field about two miles southwest of the runway. The plane hit the ground on its belly, the force of the impact flipping it onto its back and causing “total damage.” Both Zeigler and Copeland were seriously injured. Copeland died four days later on Sunday, December 6. Zeigler passed away the following Wednesday, December 9. Colonel Francis Marion Zeigler was survived by his mother, his wife, the former Mildred Van Ausdel, a son, a step-daughter, four brothers, and four sisters. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Colonel Francis Marion Zeigler was survived by his mother, his wife, the former Mildred Van Ausdel, a son, a step-daughter, four brothers, and four sisters. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

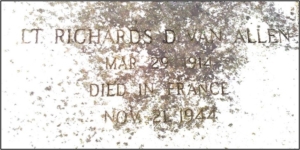

First Lieutenant Richards Daniel Van Allen was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his mother, his wife Dorothy, and a daughter, Richards Dorothy Van Allen who was born after his untimely death. Van Allen is buried at Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

First Lieutenant Richards Daniel Van Allen was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his mother, his wife Dorothy, and a daughter, Richards Dorothy Van Allen who was born after his untimely death. Van Allen is buried at Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000.

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000. peace and then outright war.

peace and then outright war.

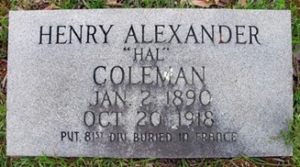

The division sailed for France in August 1918 and by early October, was defending a sector around St. Dié. Coleman, remembered as someone with a happy, optimistic disposition, was assigned as a switchboard operator, connecting calls between field phones linked by wires running through the trenches and dugouts scarring the battlefront. His switchboard was located in a muddy, dank, subterranean dugout. These conditions, combined with physical fatigue, probably contributed to a weakening of Coleman’s physical strength resulting in the contraction of an illness. Even so, Coleman remained at his post, continuing to facilitate the critical command and control functions between the various units of the division.

The division sailed for France in August 1918 and by early October, was defending a sector around St. Dié. Coleman, remembered as someone with a happy, optimistic disposition, was assigned as a switchboard operator, connecting calls between field phones linked by wires running through the trenches and dugouts scarring the battlefront. His switchboard was located in a muddy, dank, subterranean dugout. These conditions, combined with physical fatigue, probably contributed to a weakening of Coleman’s physical strength resulting in the contraction of an illness. Even so, Coleman remained at his post, continuing to facilitate the critical command and control functions between the various units of the division. quarters aboard troop ships. As they were mustered out of the service, the soldiers returned home to all corners of the country, carrying the flu virus with them. More than 675,000 Americans would die from the Spanish Flu, a ratio that would equate to about 2.15 million in terms of today’s population. Clemson’s Scroll of Honor includes thirty-four heroes who died during the First World War. Of these, thirteen succumbed to pneumonia.

quarters aboard troop ships. As they were mustered out of the service, the soldiers returned home to all corners of the country, carrying the flu virus with them. More than 675,000 Americans would die from the Spanish Flu, a ratio that would equate to about 2.15 million in terms of today’s population. Clemson’s Scroll of Honor includes thirty-four heroes who died during the First World War. Of these, thirteen succumbed to pneumonia. Henry Alexander Coleman was buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in France. There is also a marker placed in his memory at Antioch Cemetery in Fairfield County.

Henry Alexander Coleman was buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in France. There is also a marker placed in his memory at Antioch Cemetery in Fairfield County.

In mid-autumn of 1943, Hetrick was admitted to the post hospital for treatment of symptoms diagnosed as a cold. On October 2, during his brief hospital stay, Hetrick died from an acute heart attack. He died two days short of his thirty-sixth birthday,

In mid-autumn of 1943, Hetrick was admitted to the post hospital for treatment of symptoms diagnosed as a cold. On October 2, during his brief hospital stay, Hetrick died from an acute heart attack. He died two days short of his thirty-sixth birthday,

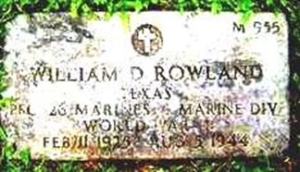

The reduced level of training received by the 79th didn’t seem to impact its combat effectiveness. A week after its commitment, the division entered the key French port of Cherbourg. It held a defensive position in early July before capturing LaHaye du Puits on July 8th. This battle pitted the infantry against German tank units in brutal fighting that cost the division more than one thousand casualties. On July 26th, the division attacked across the Ay River and took Lessay. It crossed the Sarthe River and entered Le Mans on August 8th. The division continued to advance as German resistance began to weaken, crossing the Seine River on August 19th and the Therain River on the 31st.

The reduced level of training received by the 79th didn’t seem to impact its combat effectiveness. A week after its commitment, the division entered the key French port of Cherbourg. It held a defensive position in early July before capturing LaHaye du Puits on July 8th. This battle pitted the infantry against German tank units in brutal fighting that cost the division more than one thousand casualties. On July 26th, the division attacked across the Ay River and took Lessay. It crossed the Sarthe River and entered Le Mans on August 8th. The division continued to advance as German resistance began to weaken, crossing the Seine River on August 19th and the Therain River on the 31st.

In September 1944, Allied forces in France were attacking across a broad front, slowly pushing stubborn German defenders back across France toward the Rhine River and the German border. Second Lieutenant Henry Tutt Hahn was a tank commander in the 7

In September 1944, Allied forces in France were attacking across a broad front, slowly pushing stubborn German defenders back across France toward the Rhine River and the German border. Second Lieutenant Henry Tutt Hahn was a tank commander in the 7 division was quickly committed to the battle, driving on the city of Chartres on August 18.

division was quickly committed to the battle, driving on the city of Chartres on August 18.

Pugh Rogers studied engineering at Clemson beginning in 1928. He left school after three years, but his engineering background helped prepare him for his wartime duties. Pugh was an Army Air Force master sergeant and crew chief. It was his job to supervise and lead a team of mechanics, armorers, technicians, and fuelers who often worked through the night to keep one of the squadron’s B-26 Martin bombers flying.

Pugh Rogers studied engineering at Clemson beginning in 1928. He left school after three years, but his engineering background helped prepare him for his wartime duties. Pugh was an Army Air Force master sergeant and crew chief. It was his job to supervise and lead a team of mechanics, armorers, technicians, and fuelers who often worked through the night to keep one of the squadron’s B-26 Martin bombers flying.

By the summer of 1996, Captain Earnest was assigned to Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, Texas. On Saturday, August 17, Earnest and his crew of seven other Air Force personnel, were dispatched to Jackson Hole Airport to load one of the presidential security vehicles into their C-130 Hercules transport aircraft and deliver it to New York City, the president’s next scheduled stop. Jackson Hole’s is the only airport located wholly inside a national park. It rests on a plateau near the base of the spectacular Tetons mountain range, the peaks of which rise to heights of more than 13,700 feet.

By the summer of 1996, Captain Earnest was assigned to Dyess Air Force Base in Abilene, Texas. On Saturday, August 17, Earnest and his crew of seven other Air Force personnel, were dispatched to Jackson Hole Airport to load one of the presidential security vehicles into their C-130 Hercules transport aircraft and deliver it to New York City, the president’s next scheduled stop. Jackson Hole’s is the only airport located wholly inside a national park. It rests on a plateau near the base of the spectacular Tetons mountain range, the peaks of which rise to heights of more than 13,700 feet.

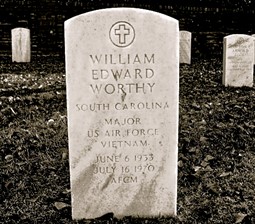

Worthy graduated and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Force on June 5, 1955. He reported for active duty and was sent to Harlingen Air Force Base, Texas to train as a bomber/navigator on the B-52 Stratofortress. Operational assignments as a B-52 navigator followed in Oklahoma and Ohio. Worthy then earned an MBA degree from the University of Oklahoma before shipping out to Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii for a tour of duty as navigator on a C-124 cargo aircraft. He was awarded the Air Medal for meritorious achievement while serving with the 50th Military Airlift Squadron and displaying outstanding airmanship and courage under extremely hazardous conditions.

Worthy graduated and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Air Force on June 5, 1955. He reported for active duty and was sent to Harlingen Air Force Base, Texas to train as a bomber/navigator on the B-52 Stratofortress. Operational assignments as a B-52 navigator followed in Oklahoma and Ohio. Worthy then earned an MBA degree from the University of Oklahoma before shipping out to Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii for a tour of duty as navigator on a C-124 cargo aircraft. He was awarded the Air Medal for meritorious achievement while serving with the 50th Military Airlift Squadron and displaying outstanding airmanship and courage under extremely hazardous conditions. the Air Medal, he was awarded the Air Force Commendation Medal with One Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with One Oak Leaf Cluster, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Air Force Longevity Service Award with Two Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Small Arms Expert Marksmanship Award. He is buried in the Florence National Cemetery.

the Air Medal, he was awarded the Air Force Commendation Medal with One Oak Leaf Cluster, Air Force Outstanding Unit Award with One Oak Leaf Cluster, National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, Air Force Longevity Service Award with Two Oak Leaf Clusters, and the Small Arms Expert Marksmanship Award. He is buried in the Florence National Cemetery.

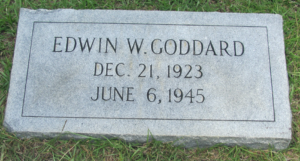

Goddard’s mission on that Wednesday was to instruct cadet Vincent Finewood in the AT-6 Texan, a single-engine advanced trainer aircraft widely used by both the Army Air Force and the Navy. Of course, given the pace of training, Goddard and Finewood weren’t the only crew in the air that day. Instructor pilot Second Lieutenant Frederick Schaeffer was also aloft in an AT-6 with his student, aviation cadet Jack Gibbs. In both cases, the instructors, Goddard and Schaeffer, were in the front seat of their aircraft, while the students were in the back seats. The AT-6 is a low-wing aircraft, limiting the pilots’ visibility below. At some point during the training flights, as both planes were about nine miles north of Berlin, Georgia, the two aircraft collided. All four occupants were killed and there were no witnesses to the accident. Army investigators determined that the likely cause of the crash was pilot error, that neither instructor saw the other plane as he was focusing his attention on his student.

Goddard’s mission on that Wednesday was to instruct cadet Vincent Finewood in the AT-6 Texan, a single-engine advanced trainer aircraft widely used by both the Army Air Force and the Navy. Of course, given the pace of training, Goddard and Finewood weren’t the only crew in the air that day. Instructor pilot Second Lieutenant Frederick Schaeffer was also aloft in an AT-6 with his student, aviation cadet Jack Gibbs. In both cases, the instructors, Goddard and Schaeffer, were in the front seat of their aircraft, while the students were in the back seats. The AT-6 is a low-wing aircraft, limiting the pilots’ visibility below. At some point during the training flights, as both planes were about nine miles north of Berlin, Georgia, the two aircraft collided. All four occupants were killed and there were no witnesses to the accident. Army investigators determined that the likely cause of the crash was pilot error, that neither instructor saw the other plane as he was focusing his attention on his student.

The 116th was part of the great armada of warships of every size and purpose that sailed from ports stretched across England’s south coast, from Sheerness at the mouth of the Thames River in the east to Helford in the west. As the invasion fleet headed into the English Channel on June 5, 1944, the men in the ships were headed toward what General Eisenhower, the Allied Supreme Commander, called “the Great Crusade.”

The 116th was part of the great armada of warships of every size and purpose that sailed from ports stretched across England’s south coast, from Sheerness at the mouth of the Thames River in the east to Helford in the west. As the invasion fleet headed into the English Channel on June 5, 1944, the men in the ships were headed toward what General Eisenhower, the Allied Supreme Commander, called “the Great Crusade.”

For more information about Private First Class David Aiken Crawford, Jr. see:

For more information about Private First Class David Aiken Crawford, Jr. see:

By the winter of 1943, Taylor was a first lieutenant assigned to VMSB 144, a Marine scouting/bombing squadron based at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The squadron, flying Douglas Dauntless SBD-4 dive bombers, completed its first combat tour in mid-March and then joined its ground echelon on Efate, in the South Pacific some 400 miles northeast of New Caledonia on the eastern edge of the Coral Sea.

By the winter of 1943, Taylor was a first lieutenant assigned to VMSB 144, a Marine scouting/bombing squadron based at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. The squadron, flying Douglas Dauntless SBD-4 dive bombers, completed its first combat tour in mid-March and then joined its ground echelon on Efate, in the South Pacific some 400 miles northeast of New Caledonia on the eastern edge of the Coral Sea.

On the morning of May 12, 1944, First Lieutenant Carson was assigned as the pilot of an RB-34 twin engine aircraft for a radar training mission. The RB-34 was a radar-equipped version of the Lockheed Ventura medium bomber. In addition to Carson at the controls of the aircraft, eight other crew members and trainees were aboard.

On the morning of May 12, 1944, First Lieutenant Carson was assigned as the pilot of an RB-34 twin engine aircraft for a radar training mission. The RB-34 was a radar-equipped version of the Lockheed Ventura medium bomber. In addition to Carson at the controls of the aircraft, eight other crew members and trainees were aboard.

snipers. The 374th Battalion history described him as “one of our best boys.” The following day, the 374th, after a record-setting 178 consecutive days on the line, was pulled out and placed in the 7th Army’s reserve.

snipers. The 374th Battalion history described him as “one of our best boys.” The following day, the 374th, after a record-setting 178 consecutive days on the line, was pulled out and placed in the 7th Army’s reserve.

two brothers, and three sisters. After the war, his remains were returned to the United States and laid to rest in the Columbia Baptist Church Cemetery.

two brothers, and three sisters. After the war, his remains were returned to the United States and laid to rest in the Columbia Baptist Church Cemetery. homeland invaded, Hitler and his Nazi cronies were unwilling to face the reality of their dire circumstances. They refused to give up and so the fighting and the dying continued. Thomas Edward Davis, Jr. was one of the junior officers leading the Allied offensive inside Germany.

homeland invaded, Hitler and his Nazi cronies were unwilling to face the reality of their dire circumstances. They refused to give up and so the fighting and the dying continued. Thomas Edward Davis, Jr. was one of the junior officers leading the Allied offensive inside Germany.

With Germany far from defeated, the need for replacements, particularly among the infantry, was acute. To meet the increasing manpower need, the Army shipped individual replacements to existing divisions and deployed fresh divisions that had been organized and trained in the United States. Second Lieutenant David Alexander was assigned to the 71st Infantry Division which was among the last US infantry divisions committed to combat in Europe. It arrived at Le Havre, France in early February 1945. After in-theater training, the 71st moved east in March and relieved the 100th Infantry Division at Ratzwiller in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France. The mission of the 71st was to continue to push the Germans out of France, across the Rhine River, and into Germany.

With Germany far from defeated, the need for replacements, particularly among the infantry, was acute. To meet the increasing manpower need, the Army shipped individual replacements to existing divisions and deployed fresh divisions that had been organized and trained in the United States. Second Lieutenant David Alexander was assigned to the 71st Infantry Division which was among the last US infantry divisions committed to combat in Europe. It arrived at Le Havre, France in early February 1945. After in-theater training, the 71st moved east in March and relieved the 100th Infantry Division at Ratzwiller in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France. The mission of the 71st was to continue to push the Germans out of France, across the Rhine River, and into Germany.

Germany as the copilot of Pegasus Too, piloted by First Lieutenant L. Wilson. From 0600 to 0651 on March 23, 1944, thirty-one aircraft took off from the 388th’s base. Assembling into formation without difficulty, the aircraft turned to the east. According to the group’s mission report, the formation crossed the enemy coast ahead of schedule. This efficiency led to disaster. “Consequently,” the report continues, “no friendly fighter escort was met until the formation was near the IP,” the point from which its bomb run commenced. As a result, thirty-five to forty-five enemy fighters, mostly Focke-Wulf 190s, attacked the formation between 0955 and 1010 hours. “The attacks were vicious.” The German fighters attacked from above and to the left front of the bombers. Two of the bombers were shot down. Coleman’s aircraft, however, was attacked in a less conventional manner.

Germany as the copilot of Pegasus Too, piloted by First Lieutenant L. Wilson. From 0600 to 0651 on March 23, 1944, thirty-one aircraft took off from the 388th’s base. Assembling into formation without difficulty, the aircraft turned to the east. According to the group’s mission report, the formation crossed the enemy coast ahead of schedule. This efficiency led to disaster. “Consequently,” the report continues, “no friendly fighter escort was met until the formation was near the IP,” the point from which its bomb run commenced. As a result, thirty-five to forty-five enemy fighters, mostly Focke-Wulf 190s, attacked the formation between 0955 and 1010 hours. “The attacks were vicious.” The German fighters attacked from above and to the left front of the bombers. Two of the bombers were shot down. Coleman’s aircraft, however, was attacked in a less conventional manner.

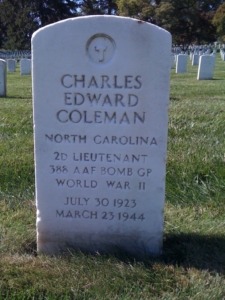

Second Lieutenant Charles Edward Coleman was awarded the Purple Heart. He was survived by his wife and his parents. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Second Lieutenant Charles Edward Coleman was awarded the Purple Heart. He was survived by his wife and his parents. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

When Ben’s friend Ernie Pyle, the famous Scripps-Howard columnist, arrived to cover the Blitz, Ben showed him how to navigate wartime London. “I feel like a mental child beside them,” Pyle wrote of his correspondent colleagues. “Yet I discovered that almost without exception they are friendly and helpful. And I discovered that among them almost nobody stands higher than my one old friend in London, Ben Robertson of PM.”

When Ben’s friend Ernie Pyle, the famous Scripps-Howard columnist, arrived to cover the Blitz, Ben showed him how to navigate wartime London. “I feel like a mental child beside them,” Pyle wrote of his correspondent colleagues. “Yet I discovered that almost without exception they are friendly and helpful. And I discovered that among them almost nobody stands higher than my one old friend in London, Ben Robertson of PM.” Terminal at New York’s Municipal Airport. Technically under the control of the Army, the Clippers though still crewed and piloted by Pan Am employees, were reserved for official government travel. Ben had waited for several days for his turn to board the big aircraft for its flight to Europe. Bound for Lisbon in neutral Portugal, Ben’s flight stopped first in Bermuda and then in the Azores before completing its journey on Lisbon’s Tagus River. The Clipper was a luxurious aircraft which had inaugurated trans-Atlantic passenger service. It was noted for aerial elegance, from its dining room to its sleeping berths. Settling into his seat, Ben looked across the narrow aisle to discover that his neighbor was Jane Froman, the prominent singer and a friend of Ben’s from their days together at the University of Missouri. Froman was bound for Europe with a USO troupe scheduled to perform for American military personnel.

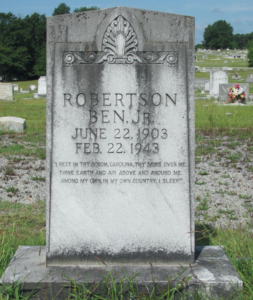

Terminal at New York’s Municipal Airport. Technically under the control of the Army, the Clippers though still crewed and piloted by Pan Am employees, were reserved for official government travel. Ben had waited for several days for his turn to board the big aircraft for its flight to Europe. Bound for Lisbon in neutral Portugal, Ben’s flight stopped first in Bermuda and then in the Azores before completing its journey on Lisbon’s Tagus River. The Clipper was a luxurious aircraft which had inaugurated trans-Atlantic passenger service. It was noted for aerial elegance, from its dining room to its sleeping berths. Settling into his seat, Ben looked across the narrow aisle to discover that his neighbor was Jane Froman, the prominent singer and a friend of Ben’s from their days together at the University of Missouri. Froman was bound for Europe with a USO troupe scheduled to perform for American military personnel. The SS Ben Robertson, a Liberty ship, was launched from Savannah, Georgia in January 1944 and served both the Normandy landings and operations in the Pacific. It is a fitting honor to a man who traveled on and over the seas, but perhaps the most poignant tribute was paid by his friend Murrow. On one of his broadcasts to America, Murrow described Robertson as “the least hard-boiled newspaperman I have ever known. He didn’t need to be, for his roots were deep in the red soil of Carolina, and he had a faith that is denied to many of us.” Murrow’s deep, familiar voice crackled over the airwaves, “There never was a night so black Ben couldn’t see the stars.”

The SS Ben Robertson, a Liberty ship, was launched from Savannah, Georgia in January 1944 and served both the Normandy landings and operations in the Pacific. It is a fitting honor to a man who traveled on and over the seas, but perhaps the most poignant tribute was paid by his friend Murrow. On one of his broadcasts to America, Murrow described Robertson as “the least hard-boiled newspaperman I have ever known. He didn’t need to be, for his roots were deep in the red soil of Carolina, and he had a faith that is denied to many of us.” Murrow’s deep, familiar voice crackled over the airwaves, “There never was a night so black Ben couldn’t see the stars.”

Moise was immediately assigned to a minesweeper serving in Japanese waters. After the war’s conclusion, as the Navy reduced its strength, Moise was put in command of the ship for its return voyage to Charleston Navy Base. Following an assignment in underwater research at Hampton, Virginia, Moise requested and was granted a transfer to the Navy’s aviation arm. On December 21, 1948, Moise married Betty Garris of Andrews.

Moise was immediately assigned to a minesweeper serving in Japanese waters. After the war’s conclusion, as the Navy reduced its strength, Moise was put in command of the ship for its return voyage to Charleston Navy Base. Following an assignment in underwater research at Hampton, Virginia, Moise requested and was granted a transfer to the Navy’s aviation arm. On December 21, 1948, Moise married Betty Garris of Andrews. routine armaments test. The Savage was a medium bomber designed to carry atomic bombs from the decks of Navy aircraft carriers. As such, it was at the time of its development the heaviest aircraft to operate from a carrier. It was powered by two wing-mounted piston engines plus a turbojet incorporated into the rear of the fuselage.

routine armaments test. The Savage was a medium bomber designed to carry atomic bombs from the decks of Navy aircraft carriers. As such, it was at the time of its development the heaviest aircraft to operate from a carrier. It was powered by two wing-mounted piston engines plus a turbojet incorporated into the rear of the fuselage. For more information about Lieutenant Moise McFaddin see:

For more information about Lieutenant Moise McFaddin see: collegiate career interrupted by orders from the War Department. All junior cadets and underclassmen were sent to basic training. Those like Henry Laye, who demonstrated military aptitude, were subsequently ordered to officers’ candidate schools to become the junior leaders of the still expanding Army. Henry Laye would soon be assigned to one of the Army’s storied divisions, the 42nd Infantry.

collegiate career interrupted by orders from the War Department. All junior cadets and underclassmen were sent to basic training. Those like Henry Laye, who demonstrated military aptitude, were subsequently ordered to officers’ candidate schools to become the junior leaders of the still expanding Army. Henry Laye would soon be assigned to one of the Army’s storied divisions, the 42nd Infantry. division arrived at Marseille, France on December 8-9, 1944 and was under the command of General Alexander Patch’s 7th Army. On Christmas Eve, the division relieved the 36th Infantry Division, entering combat in the vicinity of Strasbourg, the French city resting on the west bank of the Rhine River directly across from Germany. Most of the action at that moment was farther north, where what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge was raging. Before long, the desperate Germans, formerly masters of Europe but now reeling from the Anglo-American offensive in the west and the Soviet onslaught from the east, would attempt yet another counter-offensive, Operation Northwind.

division arrived at Marseille, France on December 8-9, 1944 and was under the command of General Alexander Patch’s 7th Army. On Christmas Eve, the division relieved the 36th Infantry Division, entering combat in the vicinity of Strasbourg, the French city resting on the west bank of the Rhine River directly across from Germany. Most of the action at that moment was farther north, where what would become known as the Battle of the Bulge was raging. Before long, the desperate Germans, formerly masters of Europe but now reeling from the Anglo-American offensive in the west and the Soviet onslaught from the east, would attempt yet another counter-offensive, Operation Northwind. on the west bank of the Rhine River when Germans from the 7th Parachute Division attacked. In three days of attacks and counterattacks in the cold, snowy villages and woodlands along the river, the Germans were driven off, but the regiment took many casualties, including Laye.

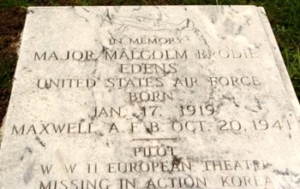

on the west bank of the Rhine River when Germans from the 7th Parachute Division attacked. In three days of attacks and counterattacks in the cold, snowy villages and woodlands along the river, the Germans were driven off, but the regiment took many casualties, including Laye. member of Company C, 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment of the Corps of Cadets, but no picture identified as Edens is included in the annual. Edens was among that large group of Clemson cadets whose educations were interrupted by World War II. In Edens’s case, the interruption was voluntary. Following stints at Presbyterian College and then Clemson, Edens dropped out of school in October 1941, even before the United States was dragged into the war. Conflicting accounts of Edens’s history pop up at this point. Although his home was in Pumpkintown in Pickens County, one account shows Edens enlisting in Miami, Florida while another places his enlistment at Fort McPherson, Georgia. Regardless of the location, Edens volunteered for the Army Air Force and was accepted into the aviation cadet program.

member of Company C, 1st Battalion, 1st Regiment of the Corps of Cadets, but no picture identified as Edens is included in the annual. Edens was among that large group of Clemson cadets whose educations were interrupted by World War II. In Edens’s case, the interruption was voluntary. Following stints at Presbyterian College and then Clemson, Edens dropped out of school in October 1941, even before the United States was dragged into the war. Conflicting accounts of Edens’s history pop up at this point. Although his home was in Pumpkintown in Pickens County, one account shows Edens enlisting in Miami, Florida while another places his enlistment at Fort McPherson, Georgia. Regardless of the location, Edens volunteered for the Army Air Force and was accepted into the aviation cadet program.

Pumpkintown.

Pumpkintown. of 1944. But the Allied offensive in Northern France was slowed by its very success; the more ground the Anglo-American forces gained, the longer their supply lines stretched and the more difficult it became to feed, fuel, and equip the advance. First Lieutenant Archibald Carlisle Dudley of Mullins was an infantry platoon leader in the van of the Allied assault.

of 1944. But the Allied offensive in Northern France was slowed by its very success; the more ground the Anglo-American forces gained, the longer their supply lines stretched and the more difficult it became to feed, fuel, and equip the advance. First Lieutenant Archibald Carlisle Dudley of Mullins was an infantry platoon leader in the van of the Allied assault.

vigilant witness to the sacrifice of American lives in World War II’s struggle against tyranny. More than 5,200 American service members are buried on the pristine acres of the Epinal American Cemetery, including Albert Powhatan King, Jr. of Ninety Six.

vigilant witness to the sacrifice of American lives in World War II’s struggle against tyranny. More than 5,200 American service members are buried on the pristine acres of the Epinal American Cemetery, including Albert Powhatan King, Jr. of Ninety Six. On Sunday, November 19, the 79th broke through to Sarrebourg, just 40 miles west of Strasbourg. Allied artillery overwhelmed German defenders, opening the road to Strasbourg. As the Germans withdrew, the 79th moved in. Four days later, as King’s Company C of the 313th Infantry Regiment enjoyed its Thanksgiving lunch, orders came to move into an area that the regiment believed was secure. The company moved out in a convoy with Captain King guiding the way in the lead jeep. As King stood to direct his company, a German sniper shot him through the forehead. King exclaimed, “Oh my God, men!”—and died. He was buried with full military honors the following day at Epinal.

On Sunday, November 19, the 79th broke through to Sarrebourg, just 40 miles west of Strasbourg. Allied artillery overwhelmed German defenders, opening the road to Strasbourg. As the Germans withdrew, the 79th moved in. Four days later, as King’s Company C of the 313th Infantry Regiment enjoyed its Thanksgiving lunch, orders came to move into an area that the regiment believed was secure. The company moved out in a convoy with Captain King guiding the way in the lead jeep. As King stood to direct his company, a German sniper shot him through the forehead. King exclaimed, “Oh my God, men!”—and died. He was buried with full military honors the following day at Epinal. Benning, Georgia. King’s Clemson story did not end with his death. His former Clemson roommate, James MacMillan, married his widow Bess after the war. King’s daughter Nancy was one of the first women accepted to Clemson, though the college’s lack of a nursing curriculum led her to enroll elsewhere. In all more than a dozen of King’s relatives subsequently attended Clemson.

Benning, Georgia. King’s Clemson story did not end with his death. His former Clemson roommate, James MacMillan, married his widow Bess after the war. King’s daughter Nancy was one of the first women accepted to Clemson, though the college’s lack of a nursing curriculum led her to enroll elsewhere. In all more than a dozen of King’s relatives subsequently attended Clemson.

Furman joined the crew of “Tillie,” a B-24D heavy bomber which he served as radio operator and waist gunner. Furman’s unit, the 372nd Bomb Squadron, was operating from Noemfoor, a small island off the northern coast of New Guinea. On November 4, Furman was seriously injured in an aircraft accident that resulted in the scrapping of “Tillie.” Furman’s injuries were significant enough to land him in the hospital, where he died three days later.

Furman joined the crew of “Tillie,” a B-24D heavy bomber which he served as radio operator and waist gunner. Furman’s unit, the 372nd Bomb Squadron, was operating from Noemfoor, a small island off the northern coast of New Guinea. On November 4, Furman was seriously injured in an aircraft accident that resulted in the scrapping of “Tillie.” Furman’s injuries were significant enough to land him in the hospital, where he died three days later.

Rudolf Anderson, Jr. Anderson, a 1948 graduate in textile management, was the sole casualty in the Cuban Missile Crisis which pushed the United States and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war sixty years ago this week.

Rudolf Anderson, Jr. Anderson, a 1948 graduate in textile management, was the sole casualty in the Cuban Missile Crisis which pushed the United States and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war sixty years ago this week. Force Base in Texas where he earned his wings in February 1953. He was next sent to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada where he learned to fly the F-86 Sabre, the Air Force’s primary air combat fighter of the Korean War.

Force Base in Texas where he earned his wings in February 1953. He was next sent to Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada where he learned to fly the F-86 Sabre, the Air Force’s primary air combat fighter of the Korean War. CIA photo interpreters identified Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles being installed near San Cristobal, Cuba. In addition, Soviet surface-to-air missile defenses were being set up, though neither weapons system was as yet operational. These discoveries triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis—and would cost Rudy Anderson’s life.

CIA photo interpreters identified Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missiles being installed near San Cristobal, Cuba. In addition, Soviet surface-to-air missile defenses were being set up, though neither weapons system was as yet operational. These discoveries triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis—and would cost Rudy Anderson’s life.

long drive to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There, they intended to rendezvous with Rebecca’s husband, Clinton Childs Horton, Jr., then serving as a doctor in the Naval Reserve. The reunion never took place.

long drive to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There, they intended to rendezvous with Rebecca’s husband, Clinton Childs Horton, Jr., then serving as a doctor in the Naval Reserve. The reunion never took place.

cohort to complete its academic career until after the war. Following commencement, Claude and his classmates headed directly to active duty, many of them funneling into officers’ candidate schools. Most of the other boys on campus were sent to basic training, their school days suspended for the duration.

cohort to complete its academic career until after the war. Following commencement, Claude and his classmates headed directly to active duty, many of them funneling into officers’ candidate schools. Most of the other boys on campus were sent to basic training, their school days suspended for the duration. Furman. In a sign of the times, Clemson also took the field against a team from Jacksonville Naval Air Station, losing 24-6. At the end of the season, Rothell and his teammates must have turned their thoughts toward the deadlier opponents that awaited overseas.

Furman. In a sign of the times, Clemson also took the field against a team from Jacksonville Naval Air Station, losing 24-6. At the end of the season, Rothell and his teammates must have turned their thoughts toward the deadlier opponents that awaited overseas. Clemson classmate Henry Hahn, who was assigned to one of the 7th Armored Division’s tank battalions.

Clemson classmate Henry Hahn, who was assigned to one of the 7th Armored Division’s tank battalions. volcanic islands in the Marianas chain. The island was part of a League of Nations mandate granted to Japan after its participation in the Great War as a member of the victorious Allied powers. That same year, Louis Gray Clark of Walhalla enrolled in Clemson College.

volcanic islands in the Marianas chain. The island was part of a League of Nations mandate granted to Japan after its participation in the Great War as a member of the victorious Allied powers. That same year, Louis Gray Clark of Walhalla enrolled in Clemson College. On August 22, 1944, Second Lieutenant Clark was ordered on a mission to attack the Japanese airfield on Pagan Island, some two hundred miles north of Saipan. He was slotted to fly as wingman to First Lieutenant Earl Harbour. The flight departed Saipan’s East Field and flew north. At about 1030 hours, Harbour completed a strafing pass from east-to-west over the Pagan airfield. When he looked back to check on his wingman, he saw Clark’s P-47 go into the water. Harbour saw Clark, under a parachute, drop into the sea only a quarter of a mile from the west-southwest shore of the island. Harbour orbited his wingman’s position and observed Clark floating in the water with his life vest inflated. Shortly thereafter, Harbour lost sight of Clark. Additional P-47s joined the search, as did a Navy PBM rescue plane. The search continued into the afternoon, but was called off at nightfall. Because the search planes were fired upon by Pagan’s Japanese defenders, Harbour speculated that Clark had either been captured by the Japanese or killed in the water by enemy fire. Clark was never recovered.

On August 22, 1944, Second Lieutenant Clark was ordered on a mission to attack the Japanese airfield on Pagan Island, some two hundred miles north of Saipan. He was slotted to fly as wingman to First Lieutenant Earl Harbour. The flight departed Saipan’s East Field and flew north. At about 1030 hours, Harbour completed a strafing pass from east-to-west over the Pagan airfield. When he looked back to check on his wingman, he saw Clark’s P-47 go into the water. Harbour saw Clark, under a parachute, drop into the sea only a quarter of a mile from the west-southwest shore of the island. Harbour orbited his wingman’s position and observed Clark floating in the water with his life vest inflated. Shortly thereafter, Harbour lost sight of Clark. Additional P-47s joined the search, as did a Navy PBM rescue plane. The search continued into the afternoon, but was called off at nightfall. Because the search planes were fired upon by Pagan’s Japanese defenders, Harbour speculated that Clark had either been captured by the Japanese or killed in the water by enemy fire. Clark was never recovered.

American units engaged in this action. Since recapturing Hue after the surprise Tet Offensive, the 1st Marines had been involved in a number of combat operations large and small. Marine casualties were reported as “light,” but they weren’t light enough.

American units engaged in this action. Since recapturing Hue after the surprise Tet Offensive, the 1st Marines had been involved in a number of combat operations large and small. Marine casualties were reported as “light,” but they weren’t light enough.