Crew Mates

Written by: Kelly Durham ’80

The first shots fired by the Germans against the English in World War II came at sea on September 3, 1939—and they came by accident. The young captain of the German submarine U-30 mistakenly identified the passenger liner Athenia as a British warship, firing two torpedoes and dispatching the vessel to the bottom of the North Atlantic. One hundred seventeen passengers and crew were killed, including twenty-eight Americans. Unwittingly, the German commander had violated the rules of submarine warfare by striking a liner without warning and without concern for the safety of its passengers and crew—a strategy that would soon be adopted by other belligerents. This was the opening encounter of the Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign of the war running from that September evening until the defeat of Germany in May 1945.

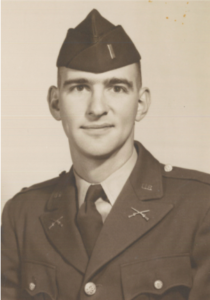

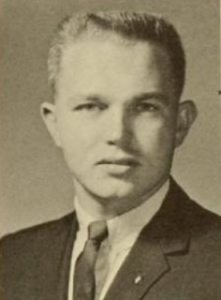

As the British battled the Germans at sea and in France, Rueben Lafayette Thomas, Jr., and his fellow cadets of Clemson’s Class of 1940 were preparing for their June 3 commencement ceremonies. Thomas, a textile engineering major from Spartanburg, soon found himself among the growing number of young men swapping their cadet uniforms for the uniform of the US Army. Thomas volunteered for the Army’s aviation program, earning his wings and being assigned to fly multi-engine bombers.

Lafayette Thomas, Jr., and his fellow cadets of Clemson’s Class of 1940 were preparing for their June 3 commencement ceremonies. Thomas, a textile engineering major from Spartanburg, soon found himself among the growing number of young men swapping their cadet uniforms for the uniform of the US Army. Thomas volunteered for the Army’s aviation program, earning his wings and being assigned to fly multi-engine bombers.

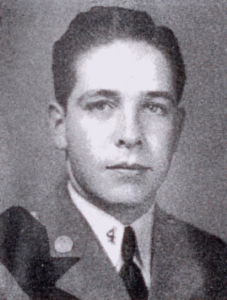

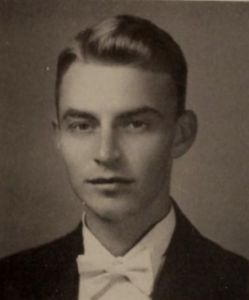

Deckerd Jefferson Gray, a general sciences major from Ware Shoals, had been a member of the cadet corps as well. A member of the Class of 1941, Gray stayed remained on campus only for his freshman year. He too soon found himself in an Army Air Forces uniform.

Fate and the crucial Battle of the Atlantic were about to bring these two Clemson men together.

The British suffered severe losses of men, ships and goods to the German U-boat fleet during the first years of the war. Numbering just fifty-seven at the war’s outbreak, the Germans’ U-boat fleet would add 1100 more boats by war’s end. Once the United States was pulled into the conflict by the Pearl Harbor attack, U-boats quickly deployed to the waters off the American east coast. There they found, initially at least, good hunting.

Beginning in January 1942, U-boats exacted a heavy toll on US and Allied merchant shipping transporting raw goods and finished products along the east coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. Over the first three months of the year, fifty-three ships were sunk. Based on March losses, the US was on pace to lose more than two million tons of shipping for the year. The “exchange rate,” defined as the ratio of merchant ships lost to U-boats sunk, would reach 89 to one for the year—a clearly unsustainable figure. American leaders scrambled to train the men and to create the organizations and equipment needed to counter the increasing U-boat threat.

The Navy had responsibility foroperations beyond the coastline, but, according to a 1945 Army Air Forces report entitled The Antisubmarine Command, “the shock of Pearl Harbor found the Navy quite unable to carry on the offshore patrol necessary to the fulfillment of its mission.” As a result, the burden for antisubmarine patrols fell mainly on the Army Air Forces whose units were neither trained nor equipped for this type of mission.

American strategists sought assistance from their British allies, whose survival as an island nation depended on defeating the U-boat menace which sought to encircle Great Britain and choke off its supply of food, petroleum and other vital goods. US forces learned from their British allies that close coordination between sea and air forces along with continuous offensive action were necessary to defeat the U-boat threat. As Army Air Forces and Navy units developed their command and control relationships and procedures, their coordinated attacks began to slowly push the U-boats out

of coastal waters.

The Army Air Forces’ 1st Bomber Command, including the 40th Bombardment Squadron, was given the task of protecting coastal shipping and attacking the U-boats. As coordination between air and sea units improved, shipping losses in coastal waters began to slowly decrease. Even as the U-boats gradually withdrew from the east coast and the Gulf, the Army established an Antisubmarine Command in November 1942.

The withdrawal of the U-boats from American waters did not mark victory in the Battle of the Atlantic, only a change of venue. German submarines continued to achieve remarkable success, sinking one hundred forty-two Allied ships in November alone, almost all of these in the North Atlantic. To help counter the continuing threat, the 40th Bombardment Squadron was redesignated the 4th Antisubmarine Squadron and moved its headquarters to the Royal Canadian Air Force base at Gander, Newfoundland. From there, the squadron flew antisubmarine patrols and convoy escort missions along North Atlantic shipping lanes.

By the spring of 1943, the Battle of the Atlantic had clearly swung in the Allies’ favor. Sinkings were down and the Allies pressed their advantage by forming the 479th Antisubmarine Group. The 4th Squadron moved its headquarters again, this time to the Royal Air Force base at Dunkeswell in southwestern England and began to hunt the hunters.

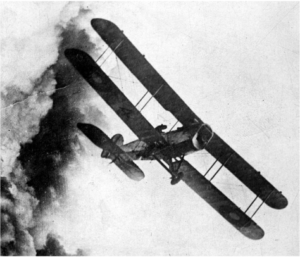

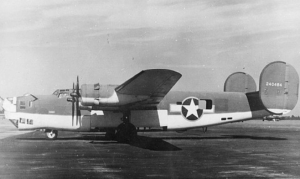

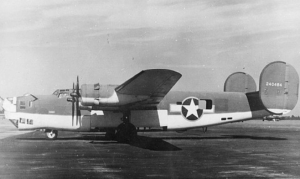

On August 8, 1943, Thomas, now a captain, the pilot of a modified B-24 heavy bomber, and a veteran of over one hundred twenty-five operational missions including eight hundred hours of combat time, took off on a patrol  mission over the Bay of Biscay. The body of water separated western France from northern Spain and included the heavily fortified German U-boat base at Brest. The B-24D Liberator bombers flown by the 4th Squadron were modified with a special radar to help the crew locate—and attack—U-boats. The radar operator assigned to this flight was Technical Sergeant Deckerd Gray.

mission over the Bay of Biscay. The body of water separated western France from northern Spain and included the heavily fortified German U-boat base at Brest. The B-24D Liberator bombers flown by the 4th Squadron were modified with a special radar to help the crew locate—and attack—U-boats. The radar operator assigned to this flight was Technical Sergeant Deckerd Gray.

Between 1159 and 1225 hours, Thomas’s aircraft radioed that it was under attack from enemy fighter planes. No additional transmissions were received and the aircraft was listed as “overdue” at 1920 hours. Over the next day and a half, search aircraft failed to find any signs of the aircraft or its crew.

Thomas, Gray and the eight other members of the crew were listed as missing. Gray was awarded the Air Medal with oak leaf clusters. Thomas was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with oak leaf clusters. The official history of the 4th Antisubmarine Squadron noted that “This was an old crew. Capt. Thomas had been in the thick of the antisubmarine warfare since Dec. 7, 1941… It was impossible to replace him…”

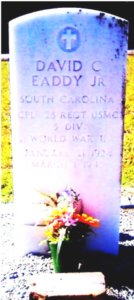

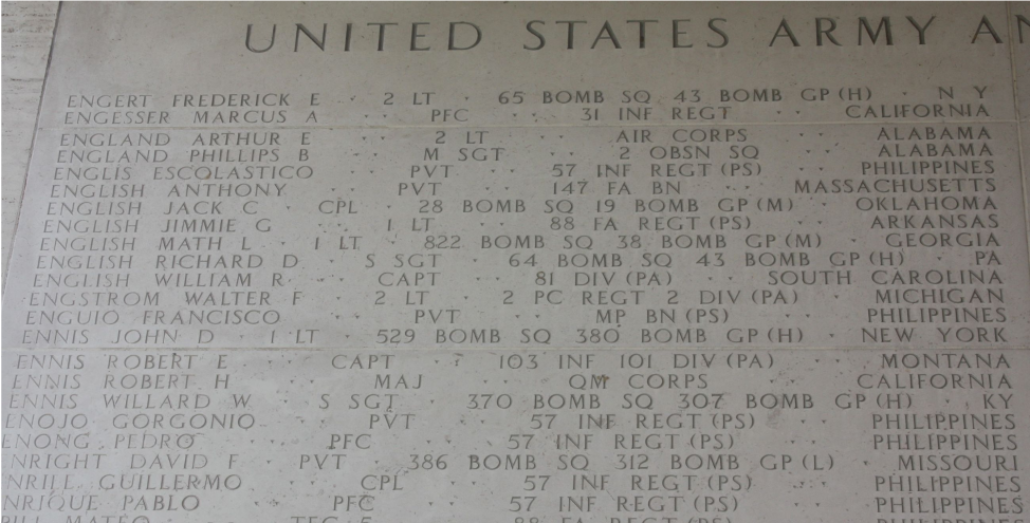

Both Gray and Thomas are memorialized at the Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England.

For more information on Deckerd Jefferson Gray visit:

https://cualumni.clemson.edu/page.aspx?pid=1606

For more information about Rueben Lafayette Thomas, Jr. see:

https://cualumni.clemson.edu/page.aspx?pid=1539

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://cualumni.clemson.edu/scrollofhonor

Additional resources: http://uboatarchive.net/

http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com (Dixie Arrow photo)

Twenty Million Tons Under the Sea: The Daring Capture of the U-505

by Daniel V. Gallery, Rear Admiral, USN (Ret.)

Raysor worked toward his degree in Chemistry, the world inched ever closer to war.

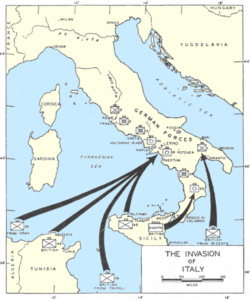

Raysor worked toward his degree in Chemistry, the world inched ever closer to war. reserve within a few days of the Sicily landings. The battalion’s soldiers were put to work guarding POW camps and supply depots, but their time in combat was not over: the invasion of Italy loomed just ahead.

reserve within a few days of the Sicily landings. The battalion’s soldiers were put to work guarding POW camps and supply depots, but their time in combat was not over: the invasion of Italy loomed just ahead.