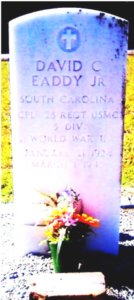

Scroll of Honor – David Clifford Eaddy, Jr.

The Last Class

Written by Kelly Durham

His was the last class to enroll at Clemson College before the war began. Most of its members would be  long gone before the day in May 1945 when they would have expected to graduate. Some, like David Clifford Eaddy , Jr. of Branchville, would never return.

long gone before the day in May 1945 when they would have expected to graduate. Some, like David Clifford Eaddy , Jr. of Branchville, would never return.

Eaddy arrived at Clemson for the fall semester in 1941. The war in Europe had been raging for nearly two years. In China, the Japanese had been on the warpath even longer, but the United States had so far managed to avoid being drawn into the war. President Roosevelt had campaigned for—and won—an unprecedented third term proclaiming that he’d kept American boys out of war. By the time Eaddy and his colleagues in the Class of 1945 had their heads shaved for their “Rat” season, Roosevelt’s promise was about to expire.

Eaddy was a vocational agriculture education major. Like many of the boys enrolling at the college, he came from a small South Carolina town. Branchville, at the southern tip of Orangeburg County, had a population of only 1,350 according to the 1940 census—making it nearly twice as large as the Clemson community Eaddy now joined. During his two years at Clemson, Eaddy was a member of the 4-H Club.

Eaddy enlisted in the Marine Corps in July 1942, training first at Emory University in Atlanta and then shipping out to California. He was assigned to the 28th Marine Regiment of the 5th Marine Division. The regiment was activated in February 1944 at Camp Pendleton, California, training there for deployment in the Pacific Theater. It boarded troop ships and sailed for Hawaii that fall. It resumed training at Camp Tarawa, Hawaii preparing for its first mission: the capture of Iwo Jima.

Iwo Jima is a volcanic island lying some 1,200 kilometers south of Tokyo. In 1945, the Japanese  were building a third airstrip on the island from which they intended to intercept US B-29 bombers flying missions against the Japanese home islands from bases on recently captured Saipan. Seizing the island would not only eliminate the threat from Japanese fighter aircraft, it would also create emergency landing fields for crippled B-29s returning from firebombing Japanese cities.

were building a third airstrip on the island from which they intended to intercept US B-29 bombers flying missions against the Japanese home islands from bases on recently captured Saipan. Seizing the island would not only eliminate the threat from Japanese fighter aircraft, it would also create emergency landing fields for crippled B-29s returning from firebombing Japanese cities.

At 0900 hours on Monday, February 19, 1945, First Battalion, 28th Marines, including Eaddy’s Baker Company, landed on Green Beach. Within two hours, Eaddy’s First Platoon had made it across the narrow southwestern neck of the island and reached the west coast of Iwo Jima. In doing so, the Marines had achieved their first day’s objectives and had isolated the dominant terrain of the island, Mount Suribachi. It took four more days for the Marines to secure Mount Suribachi, an event immortalized by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal’s dramatic shot of the mountaintop flag-raising. But the battle for Iwo Jima was just beginning.

The Japanese, knowing that reinforcement and resupply would be impossible in the face of US  air supremacy and overwhelming sea power, resolved to hold out as long as possible and to inflict unacceptable casualties on the American invaders. Japanese leaders, understanding that the war was unwinnable, hoped to convince the enemy that the cost of victory was not worth the price to be paid in young American lives. Through a fanatical defense to the death, the Japanese hoped to soften US demands for unconditional surrender. Toward that end, the defenders had honeycombed the island with interconnected caves that provided fortified, difficult to attack positions from which to fire on the Americans. One of these complexes was Hill 362A.

air supremacy and overwhelming sea power, resolved to hold out as long as possible and to inflict unacceptable casualties on the American invaders. Japanese leaders, understanding that the war was unwinnable, hoped to convince the enemy that the cost of victory was not worth the price to be paid in young American lives. Through a fanatical defense to the death, the Japanese hoped to soften US demands for unconditional surrender. Toward that end, the defenders had honeycombed the island with interconnected caves that provided fortified, difficult to attack positions from which to fire on the Americans. One of these complexes was Hill 362A.

Early on the morning of Thursday, March 1, naval ships began to bombard Hill 362A with heavy shells. Low-flying aircraft fired their machine guns and rockets and dropped bombs. Marine artillery added to the cacophony of destruction as First Battalion, including Eaddy’s Baker Company attacked. First Platoon moved around the right side of the hill as the Japanese rained down grenades, mortar rounds, and machine gun fire. The platoon leader and platoon sergeant both fell from shrapnel wounds. In the heat of the battle, three other Marines fell, including Corporal David Eaddy, leading his second squad fire team.

The Battle for Iwo Jima was unique in the United States’ island-hopping campaign of  World War II. It was the only battle in which total American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese defenders.

World War II. It was the only battle in which total American casualties exceeded those of the Japanese defenders.

David Clifford Eaddy, Jr. was survived by his parents and his sister, a student at Lander College. He was awarded the Victory Medal and the Purple Heart.

For more information about David Clifford Eaddy, Jr. see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/david-clifford-eaddy-jr/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit: