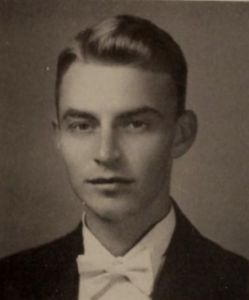

Scroll of Honor – James Crayton Herring, Jr.

Athlete, Scholar, Man of Letters

“At first we weren’t even sure there would a ‘Taps’ this year, what with a  war going on and everybody’s yelling about film and copper shortages,” wrote the editors of Clemson College’s 1943 yearbook. “But, in spite of all of our anxieties, we have succeeded in giving you an annual, one which we think compares favorably with the fine Clemson annuals of the past years. If you like it, we’re glad. If you don’t, keep it to yourself. We’ll be hard to find.”

war going on and everybody’s yelling about film and copper shortages,” wrote the editors of Clemson College’s 1943 yearbook. “But, in spite of all of our anxieties, we have succeeded in giving you an annual, one which we think compares favorably with the fine Clemson annuals of the past years. If you like it, we’re glad. If you don’t, keep it to yourself. We’ll be hard to find.”

The editors got it right. A lot of people liked the volume, for Taps was chosen, along with four others, as the best collegiate annuals in the nation for 1943. They were right in another sense as well: within weeks of graduation, they would indeed be hard to find, scattered like their classmates among military training bases all over the country as they prepared to fight a global war.

The editor-in-chief of the 1943 Taps was James Crayton Herring, Jr., a general sciences major from the Orr Mill community in Anderson. “Cotton” Herring was a noted baseball player, having played at Anderson’s Boys’ High School and for the Orr Mills and local American Legion teams as well. At Clemson, he was a four-year member of the baseball team, finishing his career on coach Frank Howard’s 12-3 1943 team.

In addition to working on the Taps staff and playing ball, Cotton  Herring was involved in a variety of other campus activities. Like all the boys of his day, Cotton was an ROTC cadet, rising to the rank of cadet second lieutenant by his senior year. He was a member of the Block C Club, Blue Key, the Anderson County Club, served as a commencement marshal, and was listed in Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges.

Herring was involved in a variety of other campus activities. Like all the boys of his day, Cotton was an ROTC cadet, rising to the rank of cadet second lieutenant by his senior year. He was a member of the Block C Club, Blue Key, the Anderson County Club, served as a commencement marshal, and was listed in Who’s Who Among Students in American Universities and Colleges.

That cloud of uncertainty that hung over the Taps staff afflicted most of the cadets on campus in the spring semester of 1943. By graduation, students, faculty and administrators knew that Clemson was undergoing an epic change. Nearly all the students would leave the campus’s rolling hills that spring. Those who would one day return would serve in all theaters of the world-wide war then consuming lives and futures at an alarming rate. And many, students and graduates alike, would never return to campus, would never return at all.

Cotton Herring was assigned as a new lieutenant to the 79th Infantry Division’s 314th Infantry Regiment. The division had been activated in June 1942 in Virginia and had trained in desert tactics in Arizona and winter operations in Kansas. In April 1944, the division departed from Massachusetts for the voyage to Great Britain. Upon its arrival in Liverpool, the division began training in amphibious operations. The division landed at Utah Beach a week after D-Day as Allied forces were  building up men and materiel and anticipating a breakout from the Normandy beachhead. The division was committed to combat on June 19 with an attack on high ground south of Cherbourg, a key harbor needed to supply invasion forces, but still held by the Germans. After a week of hard fighting, the division entered the city on June 25.

building up men and materiel and anticipating a breakout from the Normandy beachhead. The division was committed to combat on June 19 with an attack on high ground south of Cherbourg, a key harbor needed to supply invasion forces, but still held by the Germans. After a week of hard fighting, the division entered the city on June 25.

After a brief rest, the 79th resumed the offensive in early July. In its two hundred forty-eight days in combat, the 79th would suffer more than 15,000 casualties, including 2,476 killed in action—among them Cotton Herring, who was killed on July 26, just eleven days short of his twenty-first birthday, as the division was forcing the Ay River.

James Crayton Herring, Jr. was survived by his parents and his sister. For more information about James Crayton Herring, Jr. visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/james-crayton-herring-jr/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor see: