Scroll of Honor – Robert LaVerne Anderson

B-24 Gunner

Written by: Kelly Durham

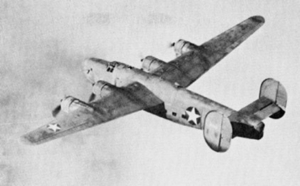

The B-17 Flying Fortress was the more famous of the American heavy bombers attacking German-occupied Europe, but its sister ship, the B-24 Liberator, carried heavier bomb loads, flew faster, and had a greater range. It was produced in greater numbers than any other American military aircraft. Robert LaVerne Anderson of Lake City was a crew member on a Liberator flying from a 15th Air Force base in Italy.

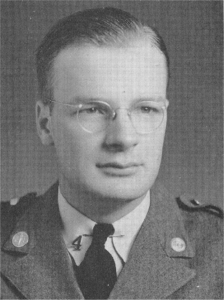

Anderson, an engineering major, attended Clemson for the 1941-42 academic year and then entered the service, volunteering for the Army Air Force. He trained as an aerial gunner and was assigned to the 758th Bomb Squadron of the 459th Bomb Group which deployed to Italy in early 1944.

B-24s of the 758th Bomb Squadron in formation.

Anderson and his comrades went to work in an “office” bristling with guns. The B-24 was armed with ten .50 caliber machine guns for self-defense: two in the nose, two in the top turret just aft of the flight deck, one on each side of the waist, two in the belly turret, and two more in the tail. The gunners, all given the rank of sergeant after

the Americans learned that captured non-commissioned officers got better treatment from the Germans than lower-ranking enlisted men, worked in an atmosphere that could be described as inhospitable. Temperatures at mission altitudes of 20,000 feet and higher plunged as low as forty degrees below zero, forcing the crew, traveling in an unheated and unpressurized aircraft, to wear electrically heated overalls beneath their heavy flying gear. Any exposed skin was susceptible to frostbite. Thinner air at these altitudes also required the crew to wear oxygen masks.

And then there were the Germans. Even in tight formations in which B-24s sought to protect themselves and each other from German fighter aircraft, losses were frequent. And though the gunners, like Anderson, could shoot back at the fighters, German anti-aircraft fire was a threat against which Anderson and the rest of the crew could offer little defense.

The job of the gunner was to protect his aircraft so that it could deliver a bomb load of up to 8,000 pounds on enemy targets like transportation hubs, airfields, aircraft factories, fuel facilities and other enemy installations deemed of value. On June 9, 1944, Anderson and the crew of Hogan’s Hellcats, a B-24 piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Walter Michaels, were assigned to bomb a target at Munich, Germany, about 500 miles north-northwest of their base at Giulia airfield outside of Cerignola, Italy.

For protection against enemy fighters, the B-24s routinely flew in well-ordered formations, with each aircraft in a position from which it could help defend not only itself, but the other planes in its flight as well. On this Friday morning, Hogan’s Hellcats was flying in the number 5 position of its formation, the third airplane on the right side of a vee-formation. Ahead about fifty yards and level with Anderson’s aircraft was another B-24. Staff Sergeant Michael Meindl was the tail gunner in this ship. Facing to the rear and scanning the skies for enemy fighters, Meindl had an excellent view of what happened as the formation released its bombs over Munich.

“After making a successful bomb run,” Meindl reported, “five bursts of flak exploded directly under Lieutenant Michaels’ ship. The tip of the left wing curled up and the ship went into about a 60% bank to the left.” Michaels brought the airplane out of its dive, but the flak had damaged the bomber and the stress on the wing caused the number 3 engine to fall off. “The last I saw of the ship,” Meindl continued, “it was spinning earthward, into the flak barrage below us.”

Only the airplane’s navigator, 2nd Lieutenant Leonard Brosky, escaped Hogan’s Hellcats, blown clear when the ship exploded. The other nine crew members were killed. They were buried near Munich. After the war, their remains were returned to the United States where they were interred at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.

For more information on Sergeant Robert LaVerne Anderson see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/robert-laverne-anderson/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/

For more information on Wilbur Harmon Creighton, Jr. see:

For more information on Wilbur Harmon Creighton, Jr. see:

On April 22, 1944, Captain Senn died from injuries sustained in a vehicle accident in Italy. He had been overseas for twenty-two months. He was buried in the National Cemetery in Bari, Italy. In 1948, Senn’s remains were returned to South Carolina and he was laid to rest in Saint Matthews’s West End Cemetery. He was survived by his wife the former Anne Power of Laurens, his parents, a sister, and a brother.

On April 22, 1944, Captain Senn died from injuries sustained in a vehicle accident in Italy. He had been overseas for twenty-two months. He was buried in the National Cemetery in Bari, Italy. In 1948, Senn’s remains were returned to South Carolina and he was laid to rest in Saint Matthews’s West End Cemetery. He was survived by his wife the former Anne Power of Laurens, his parents, a sister, and a brother.

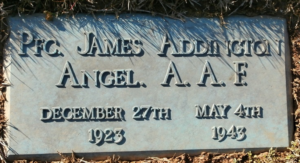

working at the aircraft plant in, ironically, Baltimore. Rhody was awarded the Purple Heart and after the war was reburied in the Silverbrook Cemetery in Anderson.

working at the aircraft plant in, ironically, Baltimore. Rhody was awarded the Purple Heart and after the war was reburied in the Silverbrook Cemetery in Anderson.

Harold Major likely headed overseas as a B-24 bomber replacement pilot in late 1944. He was assigned to the 448th Bomb Group at Seething, England about ten miles southeast of Norwich and twenty miles west of the English Channel.

Harold Major likely headed overseas as a B-24 bomber replacement pilot in late 1944. He was assigned to the 448th Bomb Group at Seething, England about ten miles southeast of Norwich and twenty miles west of the English Channel.

War I Victory Medal.

War I Victory Medal.

Cochran was assigned to the 406th Infantry Regiment of the 102nd Infantry Division organized that September at Camp Maxey in northeast Texas. After two years of stateside training, the 102nd deployed overseas arriving at Cherbourg, France in September 1944.

Cochran was assigned to the 406th Infantry Regiment of the 102nd Infantry Division organized that September at Camp Maxey in northeast Texas. After two years of stateside training, the 102nd deployed overseas arriving at Cherbourg, France in September 1944.

chaired Greenville County’s Live-at-Home program for farmers, served on the board of directors of Franklin Savings and Loan, and was a trustee of the Greenville County Library. He was a member of the Rotary Club and served on the executive board of the Blue Ridge Council of the Boy Scouts.

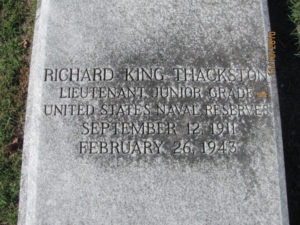

chaired Greenville County’s Live-at-Home program for farmers, served on the board of directors of Franklin Savings and Loan, and was a trustee of the Greenville County Library. He was a member of the Rotary Club and served on the executive board of the Blue Ridge Council of the Boy Scouts. in Thackston’s Chevrolet Coupe, the trio headed west on US Route 1. In the vicinity of Madison, Connecticut, they reached Jannas curve, a hazardous bend in the road.

in Thackston’s Chevrolet Coupe, the trio headed west on US Route 1. In the vicinity of Madison, Connecticut, they reached Jannas curve, a hazardous bend in the road. Lieutenant (jg) Richard King Thackston was survived by his mother and two brothers, both then serving as officers in the United States Army. He is buried in Greenville’s Christ Church Cemetery.

Lieutenant (jg) Richard King Thackston was survived by his mother and two brothers, both then serving as officers in the United States Army. He is buried in Greenville’s Christ Church Cemetery.

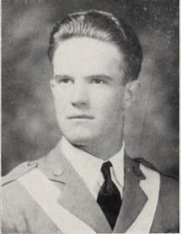

Following his commissioning as a second lieutenant in the Army Reserve and his graduation from Clemson, Jimmie returned to Augusta where he joined his father’s lumber business and worked as a general contractor. Jimmie married Connor Cleckley and was active in Augusta’s civic circles, even serving as assistant director of a boy’s summer camp.

Following his commissioning as a second lieutenant in the Army Reserve and his graduation from Clemson, Jimmie returned to Augusta where he joined his father’s lumber business and worked as a general contractor. Jimmie married Connor Cleckley and was active in Augusta’s civic circles, even serving as assistant director of a boy’s summer camp.

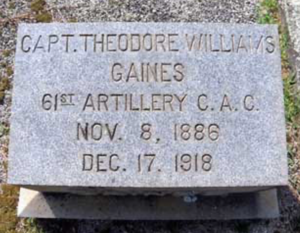

Teddy Gaines was survived by his wife and daughter, his parents, four sisters, and three brothers, two of whom, Milton and Newt, were then serving in France. He is memorialized at the Edgewood Cemetery in Greenwood.

Teddy Gaines was survived by his wife and daughter, his parents, four sisters, and three brothers, two of whom, Milton and Newt, were then serving in France. He is memorialized at the Edgewood Cemetery in Greenwood.

The troop carrier groups were expanding the role of aviation by working with the newly formed airborne units to drop paratroopers directly into combat. The 64th headed overseas in August 1942 as part of the first wave of American units to fly to Britain. Soon after its arrival, the group participated in the November invasion of North Africa, landing paratroopers on the airfield at Maison Blanche in French Algeria on November 11 and at Duzerville airfield near Bone on the following day. Subsequently, the air transport pilots ferried in fuel and anti-aircraft guns to help the paratroopers secure the airfields.

The troop carrier groups were expanding the role of aviation by working with the newly formed airborne units to drop paratroopers directly into combat. The 64th headed overseas in August 1942 as part of the first wave of American units to fly to Britain. Soon after its arrival, the group participated in the November invasion of North Africa, landing paratroopers on the airfield at Maison Blanche in French Algeria on November 11 and at Duzerville airfield near Bone on the following day. Subsequently, the air transport pilots ferried in fuel and anti-aircraft guns to help the paratroopers secure the airfields.

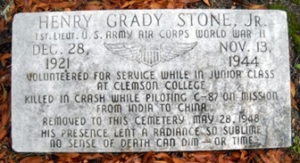

was also a member of the Flying Cadets, an organization of junior and senior cadets who already possessed their private pilot’s licenses. In that dark spring of 1942, Stone elected to depart Clemson and volunteered for the Army Air Force. Stone advanced through flight training and was designated for multi-engine flying. After earning his pilot’s wings, he completed Stateside assignments before deploying overseas in September 1944. Stone was sent to the Air Transport Command’s India-China Division to help fly supplies over “The Hump” of the Himalaya Mountains and deliver them to the Chinese.

was also a member of the Flying Cadets, an organization of junior and senior cadets who already possessed their private pilot’s licenses. In that dark spring of 1942, Stone elected to depart Clemson and volunteered for the Army Air Force. Stone advanced through flight training and was designated for multi-engine flying. After earning his pilot’s wings, he completed Stateside assignments before deploying overseas in September 1944. Stone was sent to the Air Transport Command’s India-China Division to help fly supplies over “The Hump” of the Himalaya Mountains and deliver them to the Chinese. The airplane lifted off from Jorhat Air Base at 2017 hours. Takeoff appeared to be normal with the engines running smoothly, but thirty seconds into the flight, between one and two miles from the end of the runway, the C-87 crashed, exploded, and burned, killing Stone and the two others aboard. An investigation concluded that the airplane took off with its flaps extended, increasing its drag and making it impossible to quickly climb. In addition, the investigators determined that the landing gear and the flaps could not both be retracted at the same time, so the extended gear added to the already increased drag further amplifying the difficulty of remaining aloft. It was Stone’s thirteenth mission.

The airplane lifted off from Jorhat Air Base at 2017 hours. Takeoff appeared to be normal with the engines running smoothly, but thirty seconds into the flight, between one and two miles from the end of the runway, the C-87 crashed, exploded, and burned, killing Stone and the two others aboard. An investigation concluded that the airplane took off with its flaps extended, increasing its drag and making it impossible to quickly climb. In addition, the investigators determined that the landing gear and the flaps could not both be retracted at the same time, so the extended gear added to the already increased drag further amplifying the difficulty of remaining aloft. It was Stone’s thirteenth mission.

By November, Pearce had been awarded the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters suggesting that he had completed at least fifteen combat missions. On November 3, he was promoted to first lieutenant.

By November, Pearce had been awarded the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters suggesting that he had completed at least fifteen combat missions. On November 3, he was promoted to first lieutenant. required to complete a tour of duty. He was survived by his parents and two brothers, one of whom was serving in the Navy. First Lieutenant Pearce is memorialized at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, Netherlands and at the Springwood Cemetery in Greenville.

required to complete a tour of duty. He was survived by his parents and two brothers, one of whom was serving in the Navy. First Lieutenant Pearce is memorialized at the Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, Netherlands and at the Springwood Cemetery in Greenville.

Ritchie was a Navy lieutenant (junior grade) assigned to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 33 as a naval flight officer. In Vietnam, the squadron provided carrier-based electronic countermeasure services to the fleet. The 33rd returned to Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia in 1970. Its new mission was to simulate electronic threats to units of the fleet. Participating in exercises, the 33rd’s aircraft would simulate missiles and jamming radars.

Ritchie was a Navy lieutenant (junior grade) assigned to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron 33 as a naval flight officer. In Vietnam, the squadron provided carrier-based electronic countermeasure services to the fleet. The 33rd returned to Naval Air Station Norfolk, Virginia in 1970. Its new mission was to simulate electronic threats to units of the fleet. Participating in exercises, the 33rd’s aircraft would simulate missiles and jamming radars.

Ritchie was survived by his wife and daughter. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Ritchie was survived by his wife and daughter. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

In the fall of 1944, the 502nd began to receive B-29B bombers manufactured in Marietta, Georgia. The B version of the B-29 was stripped of its high-tech electrically-fired gun system and other components in an effort to reduce weight and lessen the strain on the aircraft’s temperamental engines and airframe. Lighter and more streamlined with the elimination of gun turrets, the B-29B’s top speed increased to 364 miles per hour. The B variant was also equipped with the new AN/APQ-7 radar which provided a clearer ground image for bombing in poor visibility.

In the fall of 1944, the 502nd began to receive B-29B bombers manufactured in Marietta, Georgia. The B version of the B-29 was stripped of its high-tech electrically-fired gun system and other components in an effort to reduce weight and lessen the strain on the aircraft’s temperamental engines and airframe. Lighter and more streamlined with the elimination of gun turrets, the B-29B’s top speed increased to 364 miles per hour. The B variant was also equipped with the new AN/APQ-7 radar which provided a clearer ground image for bombing in poor visibility. son, William, then serving in the Marines. He and Bob are among the five sets of brothers listed on Clemson’s Scroll of Honor.

son, William, then serving in the Marines. He and Bob are among the five sets of brothers listed on Clemson’s Scroll of Honor.

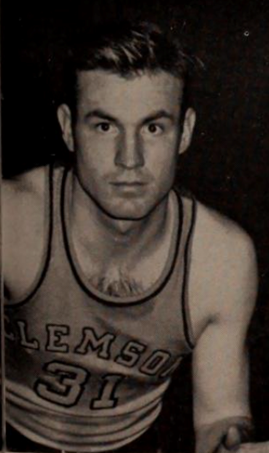

“Dub” Williams possessed the quick reflexes of a two-sport letterman. A member of Clemson’s Class of 1941, Williams was a guard on Coach Rock Norman’s basketball squad and played baseball for Coach Randy Hinson. A general science major, he was a member of the Block “C” Club and marched with the Pershing Rifles. As a junior, Williams was selected as the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment’s best drilled sergeant.

“Dub” Williams possessed the quick reflexes of a two-sport letterman. A member of Clemson’s Class of 1941, Williams was a guard on Coach Rock Norman’s basketball squad and played baseball for Coach Randy Hinson. A general science major, he was a member of the Block “C” Club and marched with the Pershing Rifles. As a junior, Williams was selected as the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment’s best drilled sergeant.

Major Walter Cleo Williams, Jr. was survived by his wife, the former Margaret Wright of Honea Path, and their daughter Peggy.

Major Walter Cleo Williams, Jr. was survived by his wife, the former Margaret Wright of Honea Path, and their daughter Peggy.

Brown’s body was one of those headed home. He was reinterred in Woodlawn Cemetery in Greenville. The final resting places of approximately 130 Clemson men lost in World War II remain scattered around the globe. More than one-third of Clemson’s World War II dead lie buried beneath the green, neatly manicured lawns of American military cemeteries in France, Belgium, Italy, Hawaii, and the Netherlands, the sandy plains of North Africa, or the rolling blue depths of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The remains of 40 of these men have never been accounted for.

Brown’s body was one of those headed home. He was reinterred in Woodlawn Cemetery in Greenville. The final resting places of approximately 130 Clemson men lost in World War II remain scattered around the globe. More than one-third of Clemson’s World War II dead lie buried beneath the green, neatly manicured lawns of American military cemeteries in France, Belgium, Italy, Hawaii, and the Netherlands, the sandy plains of North Africa, or the rolling blue depths of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The remains of 40 of these men have never been accounted for.

Two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army authorized the construction of a bomber training base at Smyrna, 25 miles southeast of Nashville, Tennessee. By the middle of 1943, the Army Air Forces’ 660th School Squadron (Special) was conducting transition training for pilots who would soon fly the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber in combat theaters.

Two weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army authorized the construction of a bomber training base at Smyrna, 25 miles southeast of Nashville, Tennessee. By the middle of 1943, the Army Air Forces’ 660th School Squadron (Special) was conducting transition training for pilots who would soon fly the B-24 Liberator heavy bomber in combat theaters. event among more than 2,000 aircraft accidents recorded by the Army Air Forces that single month. That staggering figure includes no combat accidents and is restricted to mishaps occurring in the United States.

event among more than 2,000 aircraft accidents recorded by the Army Air Forces that single month. That staggering figure includes no combat accidents and is restricted to mishaps occurring in the United States. Popeʼs body was returned to his parents, and he was buried in the Presbyterian Church Cemetery on Edisto Island. He received the World War II Victory Medal and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy, who returned to her home in Alabama following his death.

Popeʼs body was returned to his parents, and he was buried in the Presbyterian Church Cemetery on Edisto Island. He received the World War II Victory Medal and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy, who returned to her home in Alabama following his death.

After a short rest to receive and train replacements, the 3rd Division landed at Salerno on the Italian mainland as part of General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army. The 3rd battled northward through some of the fiercest fighting of the war, reaching the Volturno River and Monte Cassino, the high ground controlled by the Germans and dominating the road to Rome. In mid-November, the 3rd was pulled from the line to rest and receive replacements.

After a short rest to receive and train replacements, the 3rd Division landed at Salerno on the Italian mainland as part of General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army. The 3rd battled northward through some of the fiercest fighting of the war, reaching the Volturno River and Monte Cassino, the high ground controlled by the Germans and dominating the road to Rome. In mid-November, the 3rd was pulled from the line to rest and receive replacements. the cost, as always, was high. The 3rd Infantry Division suffered 955 casualties on May 23, including Second Lieutenant Morgan who was killed in action. The Italian capital was liberated on June 4.

the cost, as always, was high. The 3rd Infantry Division suffered 955 casualties on May 23, including Second Lieutenant Morgan who was killed in action. The Italian capital was liberated on June 4.

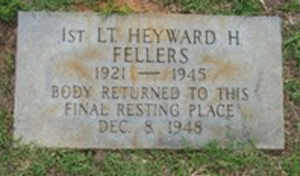

One month after graduation, Second Lieutenant Fellers reported for duty at Camp Wolters, Texas, the largest infantry replacement training center in the country. After a stint at Fort Meade, Maryland, Fellers shipped overseas in August 1944.

One month after graduation, Second Lieutenant Fellers reported for duty at Camp Wolters, Texas, the largest infantry replacement training center in the country. After a stint at Fort Meade, Maryland, Fellers shipped overseas in August 1944.

The Ventura was normally crewed by six men, but on this flight, with no operational mission en route, Staff Sergeant Lawhon and the two pilots, Second Lieutenant Joe Hanna and First Lieutenant Robert Smith, were the only official crew members. Three other service men were listed on the flight manifest as passengers. The aircraft departed Red Bluff at 1300 hours on a flight plan to Medford. With pilot Hanna at the controls, the Ventura penetrated a light overcast soon after departure and continued to climb through layers of clouds. In the vicinity of Redding, California, the weather closed in and Hanna switched to instrument flying. At this point, extreme icing conditions were encountered.

The Ventura was normally crewed by six men, but on this flight, with no operational mission en route, Staff Sergeant Lawhon and the two pilots, Second Lieutenant Joe Hanna and First Lieutenant Robert Smith, were the only official crew members. Three other service men were listed on the flight manifest as passengers. The aircraft departed Red Bluff at 1300 hours on a flight plan to Medford. With pilot Hanna at the controls, the Ventura penetrated a light overcast soon after departure and continued to climb through layers of clouds. In the vicinity of Redding, California, the weather closed in and Hanna switched to instrument flying. At this point, extreme icing conditions were encountered.

northern South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese were seeking to disrupt a vital supply link between the sea and the Marine Corps’ Dong Ha combat base in preparation for their upcoming surprise Tet Offensive.

northern South Vietnam. The North Vietnamese were seeking to disrupt a vital supply link between the sea and the Marine Corps’ Dong Ha combat base in preparation for their upcoming surprise Tet Offensive. Medal.

Medal.

Hubbard was soon ordered back to Nebraska where he received additional training in combat flying in preparation for deployment to Europe. In December 1944, Hubbard arrived in England as a pilot assigned to the 388th Bomb Squadron, an 8th Air Force unit stationed at Snetterton Heath in the southeastern part of the country.

Hubbard was soon ordered back to Nebraska where he received additional training in combat flying in preparation for deployment to Europe. In December 1944, Hubbard arrived in England as a pilot assigned to the 388th Bomb Squadron, an 8th Air Force unit stationed at Snetterton Heath in the southeastern part of the country. accidents, including eight takeoff accidents. Mercifully, not all of them were fatal.

accidents, including eight takeoff accidents. Mercifully, not all of them were fatal.

300,000 Americans who died from the Spanish Flu between September 1918 and January 1919.

300,000 Americans who died from the Spanish Flu between September 1918 and January 1919.

Zeigler’s classmates observed his “individuality, sincerity, and fineness of purpose” and elected him as president of the Class of 1923, an august group that included a future governor and US senator as well as a world famous journalist and author. Taps wrote that Zeigler had “been recognized as a leader among us, and has tackled every problem set before him in his quiet honest way.”

Zeigler’s classmates observed his “individuality, sincerity, and fineness of purpose” and elected him as president of the Class of 1923, an august group that included a future governor and US senator as well as a world famous journalist and author. Taps wrote that Zeigler had “been recognized as a leader among us, and has tackled every problem set before him in his quiet honest way.” manager of the depot’s aircraft repair shop. At approximately 1550 hours, Zeigler took off to the west. Upon reaching an altitude of twenty to thirty feet, the aircraft leveled off and then nosed down into a flat dive, striking a road about 150 feet from the end of the runway. The impact sheared off the landing gear and the faring of the right engine’s nacelle. The A-20 bounced into the air and appeared to continue straight ahead while climbing to about 200 feet. Zeigler attempted to make a wide turn to the left to return to the field, but witnesses reported that the airplane was flying in an “extremely tail low position and gradually losing altitude.” Faced with a deteriorating situation, Zeigler elected to land in a small field about two miles southwest of the runway. The plane hit the ground on its belly, the force of the impact flipping it onto its back and causing “total damage.” Both Zeigler and Copeland were seriously injured. Copeland died four days later on Sunday, December 6. Zeigler passed away the following Wednesday, December 9.

manager of the depot’s aircraft repair shop. At approximately 1550 hours, Zeigler took off to the west. Upon reaching an altitude of twenty to thirty feet, the aircraft leveled off and then nosed down into a flat dive, striking a road about 150 feet from the end of the runway. The impact sheared off the landing gear and the faring of the right engine’s nacelle. The A-20 bounced into the air and appeared to continue straight ahead while climbing to about 200 feet. Zeigler attempted to make a wide turn to the left to return to the field, but witnesses reported that the airplane was flying in an “extremely tail low position and gradually losing altitude.” Faced with a deteriorating situation, Zeigler elected to land in a small field about two miles southwest of the runway. The plane hit the ground on its belly, the force of the impact flipping it onto its back and causing “total damage.” Both Zeigler and Copeland were seriously injured. Copeland died four days later on Sunday, December 6. Zeigler passed away the following Wednesday, December 9. Colonel Francis Marion Zeigler was survived by his mother, his wife, the former Mildred Van Ausdel, a son, a step-daughter, four brothers, and four sisters. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Colonel Francis Marion Zeigler was survived by his mother, his wife, the former Mildred Van Ausdel, a son, a step-daughter, four brothers, and four sisters. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

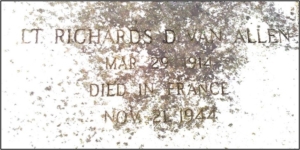

First Lieutenant Richards Daniel Van Allen was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his mother, his wife Dorothy, and a daughter, Richards Dorothy Van Allen who was born after his untimely death. Van Allen is buried at Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

First Lieutenant Richards Daniel Van Allen was awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. He was survived by his mother, his wife Dorothy, and a daughter, Richards Dorothy Van Allen who was born after his untimely death. Van Allen is buried at Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000.

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000. peace and then outright war.

peace and then outright war.

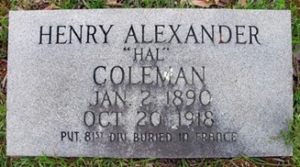

The division sailed for France in August 1918 and by early October, was defending a sector around St. Dié. Coleman, remembered as someone with a happy, optimistic disposition, was assigned as a switchboard operator, connecting calls between field phones linked by wires running through the trenches and dugouts scarring the battlefront. His switchboard was located in a muddy, dank, subterranean dugout. These conditions, combined with physical fatigue, probably contributed to a weakening of Coleman’s physical strength resulting in the contraction of an illness. Even so, Coleman remained at his post, continuing to facilitate the critical command and control functions between the various units of the division.

The division sailed for France in August 1918 and by early October, was defending a sector around St. Dié. Coleman, remembered as someone with a happy, optimistic disposition, was assigned as a switchboard operator, connecting calls between field phones linked by wires running through the trenches and dugouts scarring the battlefront. His switchboard was located in a muddy, dank, subterranean dugout. These conditions, combined with physical fatigue, probably contributed to a weakening of Coleman’s physical strength resulting in the contraction of an illness. Even so, Coleman remained at his post, continuing to facilitate the critical command and control functions between the various units of the division. quarters aboard troop ships. As they were mustered out of the service, the soldiers returned home to all corners of the country, carrying the flu virus with them. More than 675,000 Americans would die from the Spanish Flu, a ratio that would equate to about 2.15 million in terms of today’s population. Clemson’s Scroll of Honor includes thirty-four heroes who died during the First World War. Of these, thirteen succumbed to pneumonia.

quarters aboard troop ships. As they were mustered out of the service, the soldiers returned home to all corners of the country, carrying the flu virus with them. More than 675,000 Americans would die from the Spanish Flu, a ratio that would equate to about 2.15 million in terms of today’s population. Clemson’s Scroll of Honor includes thirty-four heroes who died during the First World War. Of these, thirteen succumbed to pneumonia. Henry Alexander Coleman was buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in France. There is also a marker placed in his memory at Antioch Cemetery in Fairfield County.

Henry Alexander Coleman was buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in France. There is also a marker placed in his memory at Antioch Cemetery in Fairfield County.

In mid-autumn of 1943, Hetrick was admitted to the post hospital for treatment of symptoms diagnosed as a cold. On October 2, during his brief hospital stay, Hetrick died from an acute heart attack. He died two days short of his thirty-sixth birthday,

In mid-autumn of 1943, Hetrick was admitted to the post hospital for treatment of symptoms diagnosed as a cold. On October 2, during his brief hospital stay, Hetrick died from an acute heart attack. He died two days short of his thirty-sixth birthday,