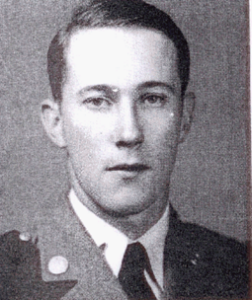

Scroll of Honor – Robert Earle Agnew

Storm Clouds

Written by: Kelly Durham

When Robert Earle Agnew arrived on the Clemson campus in 1937, the storm clouds of war were gathering. In China tensions with Japan erupted into full scale war that summer. In Europe, the German invasion of Poland in the fall of Agnew’s senior year precipitated yet another continental crisis. By the time of his graduation with the Class of 1940, France was effectively out of the war and the British were retreating to their home island. Agnew was one American who understood that those storm clouds in Asia and Europe were likely to continue to spread until they eventually reached the United States.

Agnew came to Clemson from Donalds, the small Abbeville County community of less than three hundred souls. At Clemson, he studied mechanical engineering and was a member of the track team, the Greenwood Club, and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers. During his senior year, Agnew participated in the Civilian Pilot Training Program [CPTP], a government sponsored flight training program attempting to increase the number of civilian pilots as a potential pool from which to draw military fliers if needed. Agnew was the first of the Clemson participants to solo. He also completed ROTC training at Camp McClellan, Alabama preparing Agnew for a commission in the Army.

Following graduation, Agnew reported for Army basic training. Given his CPTP experience, Agnew was accepted into Army Air Force flight training and sent to Randolph Field at San Antonio, Texas. His training continued at Kelly Field, also in San Antonio, where he earned his pilot’s wings in March 1941. In a sign of the times, the new pilot was assigned as a flight instructor and ordered to Moffett Field outside of San Jose, California. Agnew was delighted with his assignment, writing to his parents, “If I should die in a plane crash, I will die happy; everything will be all right.”

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000.

Of course, Agnew wasn’t the only observer of the gathering storm. In Washington, officials of the Roosevelt administration were scrambling to catch up with Germany’s fearsome Luftwaffe, then regarded as the most powerful air force in the world. On October 23, 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson announced plans to double the nation’s fleet of first-line combat aircraft. Noting that the increase in strength was needed to meet the “growing requirements” for adequate defense of the Western Hemisphere, Stimson explained that the Army Air Force would extend its growth plans from fifty-four combat groups to eighty-four. In the process, the number of pilots trained annually would increase from 12,000 to 30,000.

Those pilots would advance through three phases of flight training. After primary flight training in simple aircraft, phase two pilots moved into more complex trainers like the BT-13 Vultee. It was equipped with a more powerful engine, was faster and heavier than the primary aircraft, and required student pilots to manage more in-flight tasks, such as the use of flaps and a controllable-pitch propeller.

On the morning of November 3, 1941, Agnew and crew member Dan Fisk departed Stockton, California in a BT-13 Vultee bound for their home field at Moffett. The airplane never arrived. Army investigators hypothesized that Agnew was descending through or attempting to fly below storm clouds when his aircraft crashed into the side of a hill at an altitude of only 1,900 feet. Both Agnew and Fisk were killed.

Agnew would not be the last Army pilot to perish before reaching a combat zone. Training accidents would continue to plague the Army Air Force as it raced to meet the demands of an increasingly fragile  peace and then outright war.

peace and then outright war.

Robert Earle Agnew was survived by his parents and was buried in the Turkey Creek Baptist Church cemetery in Ware Shoals.

For more information on Second Lieutenant Robert Earle Agnew see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/robert-earle-agnew/

For more information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/