Scroll of Honor – Ralph Buel Bradshaw

To Them We Owe Everything

Written by: Kelly Durham

Ralph Buel Bradshaw came to Clemson in the late summer of 1938 from his hometown of Cartersville, Georgia.  Like many of the other boys in the Class of 1942, Bradshaw was an agriculture major. He remained at Clemson only for his freshman year and then returned to Cartersville and took a job processing dairy products.

Like many of the other boys in the Class of 1942, Bradshaw was an agriculture major. He remained at Clemson only for his freshman year and then returned to Cartersville and took a job processing dairy products.

In August 1941, Bradshaw left Cartersville with his friend Arthur Rhodes. The two men enlisted in the Army, reporting first to Fort McPherson south of Atlanta and then being ordered to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri for basic training. From Missouri the pair next headed to Las Vegas. Rhodes would remain there, training to become a mess sergeant. Bradshaw volunteered for the Army Air Forces and was posted as an air cadet to Gardner Field at Taft, California. Bradshaw married Sara Frances Moss of Los Angeles on July 1, 1942. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant on July 28, 1943. He would subsequently train at Luke Field in Phoenix, Arizona and at Santa Clara, California before returning to Georgia and completing his Stateside training at Waycross.

In July 1944, Second Lieutenant Bradshaw was assigned to the 65th Fighter Squadron which was part of the 12th Air Force operating from airfields on Corsica, the large island west of Italy’s Tyrrhenian Sea coast. Flying P-47 Thunderbolt fighters, the 65th carried out a variety of missions including interdiction of railroads, communications targets, and motor convoys behind enemy lines.  The P-47 was a rugged and versatile aircraft which was employed in both dive bombing and strafing missions. The squadron also supported the Allied invasion of Southern France in August 1944.

The P-47 was a rugged and versatile aircraft which was employed in both dive bombing and strafing missions. The squadron also supported the Allied invasion of Southern France in August 1944.

In September, the squadron relocated its base of operations to the Italian mainland, flying missions from Grosseto, about one hundred miles northwest of Rome. In a letter home, Bradshaw recounted a mission on which his aircraft had malfunctioned. From a high altitude, he glided to a forced landing in a forest and was able to rejoin his outfit later that same day. Letters went in both directions, of course, and Bradshaw was anticipating the one from the States that would announce the arrival of the baby Sara was carrying.

Even though Rome had been liberated in June and the Allies were advancing on practically every front, German resistance in northern Italy remained determined. The 65th’s aircraft continued to attack enemy targets in an effort to disrupt resupply and reinforcements.

On November 22, Bradshaw was assigned to fly an eight-aircraft mission to attack railroad facilities in northern Italy’s Po River Valley. At about 1300 hours, Bradshaw pushed the stick of his P-47 forward, launching the aircraft into a steep dive. Second Lieutenant Sylvester Hendricks was flying as Bradshaw’s wingman.

As we peeled off into our dive-bombing run, I followed Lt. Bradshaw down and saw him make about a 45 degree dive. He went very low and got a direct hit on the track. I saw him pull out in a very shallow pull-out straight ahead. As his bombs exploded, I saw parts fly off his airplane. It looked like about four or five feet of his left wing blew off. His aircraft did two sort of rolling tumbles to the right and started to burn badly before it hit the ground. His aircraft hit the ground about one quarter of a mile past his bomb hit. The ship did not explode but it was almost completely in flames. I did not see the pilot get out and I believe it was impossible for him to do so.

Although Bradshaw was officially listed as Missing In Action, Hendricks’ judgment proved correct. In a letter written three days after the crash, squadron commander Gilbert Wymond attempted to console Bradshaw’s father. “I know that Brad never even knew what happened as a concussion great enough to tear off a wing would positively knock the pilot out.”

Brad participated in thirty-eight missions and he inflicted heavy damage on the enemy. He was developing into a superb leader. I have seen many pilots come and go through the squadron, but none that I had more confidence in or showed more promise than Brad. … We know the anguish that is in your hearts and each and every one of us extend our deepest sympathy. Guys like Brad are saving our heritage for us; to them we owe everything.

Although “special efforts” had been made to inform Bradshaw of his daughter’s birth on November 7, a letter written by him to Sara on the night before his final mission advised that he had not yet heard the news he was so anxiously awaiting.

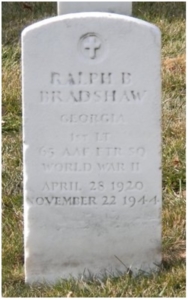

First Lieutenant Bradshaw was survived by his wife Sara and their fifteen-day-old daughter, Rita Sue. He was also survived by his parents, a sister and brother. Bradshaw was awarded the Air Medal and the Purple Heart. His body was recovered and initially buried in a civilian cemetery in Villa Poma, Italy. In 1949, Bradshaw’s remains were returned the United States and buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

For more information on Ralph Buel Bradshaw see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/ralph-buel-bradshaw/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/

P-47 photo courtesy the Imperial War Museum, http://www.americanairmuseum.com/aircraft/21479.