Scroll of Honor – Baylis Whitner Harrison, Jr.

The Most Hazardous Service

Written by: Kelly Durham

It wasn’t simply the valor of soldiers, marines, sailors, and airmen that won the Second World War.  Each combatant had to be supplied with equipment, weapons, spare parts, ammunition, uniforms, rations, medicines and all of the other various items required to keep armies in the field, aircraft in the skies, and ships on the seas. The massive logistical challenges overcome to supply American and Allied forces in a war reaching to the corners of the earth are rarely remembered today, but served as the basis for victory. The critical—and most hazardous—link in this logistical supply chain was the Merchant Marine. Baylis Whitner Harrison, Jr., was a member of Clemson’s Class of 1943 and a merchant seaman sailing on the SS John Harvey.

Each combatant had to be supplied with equipment, weapons, spare parts, ammunition, uniforms, rations, medicines and all of the other various items required to keep armies in the field, aircraft in the skies, and ships on the seas. The massive logistical challenges overcome to supply American and Allied forces in a war reaching to the corners of the earth are rarely remembered today, but served as the basis for victory. The critical—and most hazardous—link in this logistical supply chain was the Merchant Marine. Baylis Whitner Harrison, Jr., was a member of Clemson’s Class of 1943 and a merchant seaman sailing on the SS John Harvey.

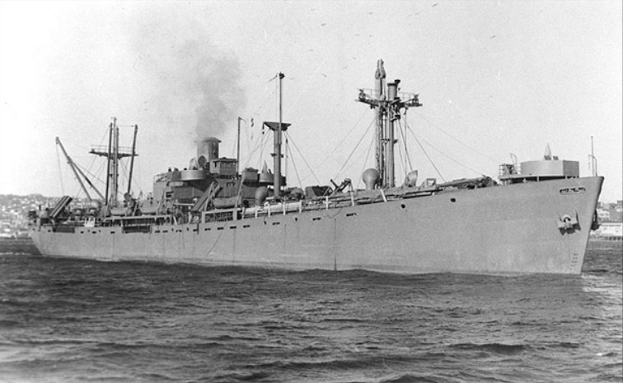

Harrison came to Clemson from his hometown of Marion, North Carolina as a freshman in 1939. He majored in civil engineering, but left campus after his first year. By 1943, when the remaining cadets in his class graduated, Harrison was serving in the Merchant Marine. His vessel, the Liberty ship John Harvey, was completed in mid-January of that year after six weeks of construction at the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company in Wilmington.

The war had put a severe strain on American shipping. Not only were massive amounts of food, weapons, ammunition and equipment needed in combat theaters, but German U-boats were sinking large numbers of US merchant vessels off America’s east coast in what the U-boat captains called “the Second Happy Time.” To meet Allied shipping needs, and fulfill its role as “the arsenal of democracy,” the United States committed to an unprecedented shipbuilding program. At its peak in 1943, American shipyards were completing more than one hundred Liberty ships per month. These ships were easy to build, reliable, and versatile. Their strength lay not in cutting edge technology, but in sheer numbers. More than twenty-seven hundred Liberty ships would be completed during the war, including the John Harvey.

The Geneva Protocol signed in 1925, had banned the use, but not the stockpiling, of chemical weapons which had been employed with devastating effect in World War I. While the United States had no intentions of offensive use of such weapons, President Roosevelt in August 1943 approved the secret shipment of mustard gas munitions to the Mediterranean theater. The mustard gas was to be positioned for retaliatory use should the Germans employ similar weapons in their defense of Italy. The SS John Harvey was selected for this classified and hazardous mission.

The ship, with Harrison aboard, sailed from Oran, Algeria on November 18, 1943. It arrived off of Bari, on Italy’s east coast, but the harbor was packed with Allied vessels unloading all manner of cargo needed to support the British and American forces then engaged against the Germans.

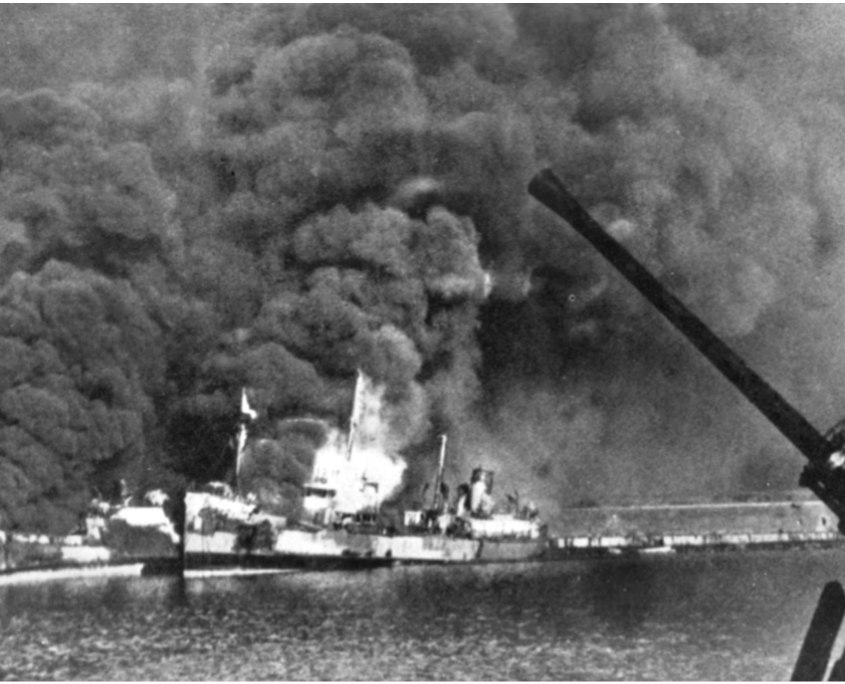

A harbor full of Allied ships proved to be a tempting target for the German Luftwaffe. The Germans were aware of the port’s inadequate anti-aircraft defenses and believed that crippling the harbor might slow the Allied advance. At 1925 hours, well after dark on December 2, one hundred fifty German Ju 88 medium bombers attacked from the east, flying over Bari from the Adriatic Sea. To facilitate unloading, the harbor was well illuminated and the German bombers had no trouble hitting their targets. Two ammunition ships exploded and a bulk petroleum pipeline was ruptured spreading a black sheet of flaming fuel over much of the harbor and engulfing previously undamaged ships. John Harvey was also hit and destroyed in an enormous blast which released liquid sulphur mustard into the harbor and into the roiling clouds of smoke generated by burning ships, dock facilities, and warehouses.

Twenty-eight merchant ships containing 31,000 tons of cargo were sunk. Another twelve were damaged. Medical authorities at Bari concentrated their treatment on those suffering from blast and fire injuries unaware that a more insidious killer was attacking sailors covered with oil from the harbor and those who had breathed in the toxic fumes mixed in with smoke from the explosions and fires. Within a day, six hundred twenty-eight patients were exhibiting symptoms of mustard gas poisoning, but medical staff members were unaware of the presence of the gas due to the highly classified nature of John Harvey’s cargo. By the end of the month, eighty-three military patients had died from mustard gas poisoning. The toll would have been higher without the efforts of Colonel Stewart Alexander, an expert in chemical warfare. Dispatched to Bari to investigate, Alexander traced the gas to John Harvey and confirmed mustard gas as the responsible agent when he located a fragment of a US mustard gas bomb. Alexander’s sleuthing alerted doctors in Bari to change their treatment to address mustard gas poisoning.

The Allied High Command attempted to conceal the disaster to avoid provoking the Germans into pre-emptive use of chemical weapons. Given the multitude of witnesses to the catastrophe, the US Chiefs of Staff finally admitted the accident in a February 1944 statement. The statement emphasized that the US had no intention of using chemical weapons except in retaliation.

Baylis Whitner Harrison, Jr.’s remains were never recovered. He was awarded the Mariner’s Medal and Combat Bar with Star.

Whether in coastal waters, on the high seas, or in the relative safety of a friendly port, merchant mariners in World War II experienced the highest casualty rate of any service. One in twenty-six merchant mariners died during the war, one reason why Congress extended veterans status to the 215,000 merchant mariners who comprised the most hazardous link in America’s wartime logistics network.

For more information about Baylis Whitner Harrison, Jr. see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/bayliss-whitner-harrison-jr/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/