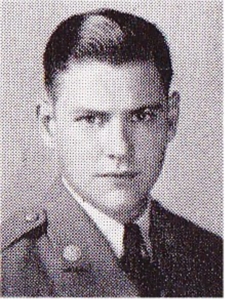

Scroll of Honor – Horace Hagood Young, Jr.

Operation RESERVIST

Written by: Kelly Durham

The first American ground forces to go into battle in the European Theater during World War II fought not the Germans,  not the Italians, but America’s oldest ally. Clemson alumnus Horace Hagood Young, Jr. Class of 1942, was a member of the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment that stormed the North African port of Oran in the early morning hours of November 8, 1942.

not the Italians, but America’s oldest ally. Clemson alumnus Horace Hagood Young, Jr. Class of 1942, was a member of the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment that stormed the North African port of Oran in the early morning hours of November 8, 1942.

Young grew up in Fairfax, graduating from high school there before enrolling at Clemson for the 1938-39 academic year. He was a cadet private in Company E majoring in general science. He did not return to campus for his sophomore year. Instead, he took a position with Thomas and Howard Company, a grocery supply business in Allendale.

It is unclear when Young began his military service, whether he volunteered or was drafted. By September 1942, he had completed his basic training and was a member of the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment, a storied unit that traced its lineage all the way back to 1789. The regiment was now part of the new 1st Armored Division. That September, the division left Fort Knox, Kentucky on its way overseas to Northern Ireland. Young and his comrades conducted additional training in the United Kingdom, but they didn’t remain there long. They were destined to take part in the first major Anglo-American invasion of the war, Operation TORCH, to seize French North Africa.

RESERVIST was the code name given the Allies’ attempt to seize intact the port of Oran on the Mediterranean coast of French Algeria. It was timed to coincide with supporting Allied landings at Algiers to the east and on the Atlantic coast of French Morocco to the west. RESERVIST was a British plan and was commanded by Royal Navy Captain Frederick Thornton Peters. The French regard for their erstwhile British allies had been shattered by the Royal Navy’s attack on the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria shortly after the French signed the armistice with Nazi Germany in June 1940. The British, fearful that the powerful fleet of their former ally would be turned over to the Germans, had attacked and sunk the French ships at the moorings. For that reason, American troops were designated to lead the assault on Oran. It was hoped that the French would give a friendlier welcome to Americans, that they might even refuse to fire.  To increase the chances of such a reception, the American soldiers would be transported aboard two Great Lakes Coast Guard cutters which had been transferred to the Royal Navy under the Lend Lease program. The two cutters, now under British command, had been renamed HMS Walney and HMS Hartland, but for this mission would fly large American flags. The problem was that the invasion was scheduled to commence in the dark of night. As British prime minister Winston Churchill warned, “In the night, all cats are grey.”

To increase the chances of such a reception, the American soldiers would be transported aboard two Great Lakes Coast Guard cutters which had been transferred to the Royal Navy under the Lend Lease program. The two cutters, now under British command, had been renamed HMS Walney and HMS Hartland, but for this mission would fly large American flags. The problem was that the invasion was scheduled to commence in the dark of night. As British prime minister Winston Churchill warned, “In the night, all cats are grey.”

The other problem was that the British had already proven the folly of a frontal assault on a defended harbor. The August raid on the French port of Dieppe had cost more than 3,500 Allied casualties, most of them Canadian. Objections to the plan came from American flag officers in both the Army and Navy, led by Rear Admiral Andrew Bennett, the senior American officer in the Oran task force. Bennett protested to General Eisenhower, Allied commander, that the plan was “suicidal and absolutely unsound.” Despite these objections, Eisenhower supported the British scheme to seize Oran’s harbor before the French could sabotage it and render it unusable.

Walney and Hartland steamed out of Gibraltar on the night of November 7, so overloaded by the contingent of American soldiers that the ships wobbled badly across the sea. At 0300 on November 8, the ships attempted to enter Oran’s harbor while broadcasting “Ne tirez pas. Nous sommes vos amis”—“Do not shoot. We are your friends.” It didn’t work.

As Hartland attempted to ram its way through the double boom protecting the harbor, French shore batteries opened fire. They were soon joined by French warships inside the port. By 0400, both Hartland and Walney were sinking. Casualties aboard the two ships topped ninety percent, a grisly score even more hideous than Dieppe’s. The first major American casualties of the war in the European Theater came not at the hands of the hated Germans or the ridiculed Italians, but from the French, the first country to come to the aid of the newly independent United States in 1777.

Horace Hagood Young died on November 8, 1942. He was awarded the Purple Heart and was survived by his mother.  He is memorialized at the North Africa American Military Cemetery in Carthage, Tunisia.

He is memorialized at the North Africa American Military Cemetery in Carthage, Tunisia.

By November 10, through diplomatic negotiations, the Allies induced the French to cease all resistance. Eisenhower, in a private meeting with the British and American chiefs of staff, took responsibility for the disaster at Oran. As historian Rick Atkinson writes, “No consequence attended the gesture.”

For more information about Private Horace Hagood Young, Jr. see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/horace-h-young/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/

For a history of Operation RESERVIST see An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942-1943, by Rick Atkinson, Henry Holt and Company, 2002.