Scroll of Honor – Derrell Sevier Jones

Whiskey Run

Written by: Kelly Durham

By mid-April 1945, the Eighth Air Force, America’s strategic bomber armada operating from English airfields, had run out of targets. So effective, so devastating had been the bombing campaign against Axis targets, that American strategic air forces in Europe switched their mission to supporting Allied ground forces. This change in tactics didn’t ground the big bombers, but it did ease the strain on its fliers as they, like so many others, waited for the inevitable German surrender.

Derrell Sevier Jones of Anderson graduated from Clemson in 1930. A horticulture major, he was a member of the Thalian Club, one of the campus’s non-fraternal social organizations which met downtown in the Masonic Lodge.

As the war in Europe struggled toward its finish, Jones was serving as a master sergeant in the 367th Bomb Squadron, the “Reich Wreckers,” based at Thurleigh Airfield in southeastern England. Jones had been awarded the Air Medal, indicating that he had completed twenty-five combat missions over Europe. On April 14, 1945, Jones departed Thurleigh on his final flight, one that was listed as a navigation training flight, but which in reality had a distinctly different purpose.

The flight, aboard a B-17G nicknamed Combined Operations, departed at 1500 hours into cloudy skies. The pilot, First Lieutenant Robert Vieille, was briefed that lower clouds along his planned route would necessitate flying at an altitude of six thousand feet. That route was to the northwest, across England, to the north of Wales, over the Irish Sea, with the destination of Langford Lodge Airfield in Northern Ireland. As this was a training rather than a combat mission, the aircraft’s aerial gunners would not be aboard. Instead, the Saturday afternoon flight was accommodating several passengers bound for Northern Ireland and a weekend of rest and relaxation. The passengers included the 367th Squadron’s executive officer, its operations officer, a female American Red Cross officer on leave from France, and Derrell Jones. The flight would have had one additional passenger, but squadron flight surgeon Dr. McClung was unable to attract Lieutenant Vieille’s attention despite chasing the B-17 down the runway in a jeep. Missing the flight saved the doctor’s life.

A little more than halfway through its planned two-hour flight, Combined Operations was about four miles to the north of it briefed course. Over the sea, that would not have been remarkable, except that the aircraft was droning along only three hundred fifty feet above sea level, not the six thousand foot altitude for which it had been cleared. While heading northwest underneath the low clouds, the pilot suddenly saw land directly ahead. He pulled the airplane up and attempted to turn to the left, but his actions were too late. The big bomber skipped across the ground and slammed into a stone wall, exploding and bursting into flame. The drift off its planned heading had put the aircraft on a collision course with the Chasms, the steep, rocky southwest coast of the Isle of Man.

The noise of the explosion alerted local residents who rushed to the site. Intense flames prevented them from getting too close to the wreckage. All eleven aboard were killed.

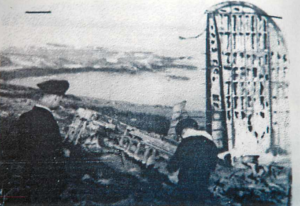

Investigators examine the crash site the following day.

The official “cover” for the flight was navigation practice. Why would an experienced pilot, copilot, and navigator be practicing navigation the day after completing a combat mission? They weren’t. The real purpose of that fatal flight had nothing to do with training and everything to do with preparing for the German surrender. That the flight was a “whiskey run” was confirmed years later by surviving members of the aircrew who didn’t go on the trip as well as other officers from the squadron. In anticipation of the end of the war—and the celebration that would accompany it—the officers of the squadron had chipped in to buy a planeload of Irish whiskey and bring it back to Thurleigh. Among the ironies of the tragic mission is that Lieutenant Vieille was a non-drinker.

Squadron commander Major Earl Kesling wrote Vieille’s father that the crash “was by far the most heartfelt accident this group ever had,” that despite the combat losses he had witnessed “never have I felt so badly about any misfortune… Army records,” Major Kesling continued, “don’t tell the whole story.” The whole story didn’t emerge until Lieutenant Vielle’s niece and her husband began to piece the story together by reviewing those “Army records” and interviewing surviving members of the squadron.

Whether Master Sergeant Jones was in on the “whiskey run” or simply an unlucky passenger is unknown. He is buried in the Cambridge American Cemetery, Cambridge, England.

For more information about Master Sergeant Derrell Sevier Jones see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/derrell-sevier-jones/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit: