Scroll of Honor – Benjamin Franklin Robertson, Jr.

“…Never Was a Night so Black…”

Written by: Kelly Durham

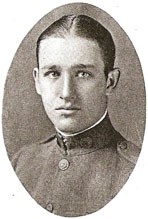

He is little known today, but at his death in early 1943, Benjamin Franklin Robertson, Jr. was arguably Clemson’s most famous son. A hometown boy, Robertson grew up in Calhoun, the tiny community just north of the railroad tracks that run through what is now more commonly known as Clemson. His father and namesake, a member of Clemson’s first graduating class in 1896, worked on campus in the office of the state chemist. Ben’s mother died on Christmas Eve 1910, perhaps from a diabetic reaction from sampling the numerous holiday cakes and pies she was preparing. Ben’s grieving father sent his son to live with the boy’s uncle in Liberty. When Robertson senior remarried in 1913, Ben and his sister Mary returned to the family’s home on Hotel Hill, overlooking the campus.

When time came for Ben to continue his education at the collegiate level, it seemed only natural that he would follow in his father’s footsteps and enroll in Clemson. Though Ben was gifted with a facility for words and literature, Clemson was an agricultural school without any liberal arts degree programs. Ben selected horticulture as his major.

According to his 1923 classmates, Ben Robertson “loved to gossip.” Even so, read his senior profile in Taps, “to know him is to like him,” a circumstance due in part to his reputation for integrity—and also perhaps because Ben knew how to have a good time. He was the founding pianist of the Jungaleers, Clemson’s dance band. “When it comes to jazzing a piano, Ben paws a mean pedal,” Taps proclaimed. Of course, Ben may have had some influence over his profile: he served as the yearbook’s editor-in-chief as a senior. He was also the associate editor of the Chronicle, the campus literary magazine. In addition to being a man of letters, Ben was a member of the Pickens County Club and the Dancing Club. He sang in the Glee Club and put his musical prowess into practice as a member of the campus orchestra.

After graduation, Robertson headed west, to the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism. After a year at Missouri, Ben returned to South Carolina. In order to gain experience and accumulate funds to return to school, he took a job with Charleston’s News and Courier where his writing , according to biographer Jodie Peeler, reflected a “personal, folksy story-telling style.” Ben returned to Missouri in 1925 and completed his degree in journalism in 1926. Ben must have been stricken with wanderlust, or perhaps a profound curiosity about the world, for he followed his graduation with a stint in Honolulu on the staff of the Star-Bulletin. In 1927, he headed west again–further west–to Adelaide, Australia. From 1929 to 1934, he reported for the New York Herald Tribune, after which he took a job with the Associated Press. He bounced over to the United Press in 1935, but two years later was back with the AP. In 1938, Robertson published his first novel, Traveler’s Rest, based on his ancestors’ experiences in South Carolina.

In 1940, following the outbreak of war in Europe, Robertson went to London to cover the story for the anti-fascist New York newspaper PM. There he came to know the most famous American correspondent of the day, Edward R. Murrow, who reported from London for CBS Radio and who would later describe Ben as his “best friend.” With Murrow, Ben would venture out of London to Shakespeare Cliff overlooking the English Channel at Dover. There they witnessed the dogfights between British and German aircraft that characterized the Battle of Britain. His observations would inform his second book, I Saw England, published in 1941. Robertson wrote:

I lost my sense of personal fear because I saw that what happened to me did not matter. We counted as individuals only as we took our place in the procession of history. It was not we who counted, it was what we stood for. And I knew for what I was standing – I was for freedom. It was as simple as that. … I understood Valley Forge and Gettysburg at Dover, and I found it lifted a tremendous weight off your spirit to find yourself willing to give up your life, if you have to – I discovered Saint Matthew’s meaning about losing a life to find it. I don’t see now why I should ever again be afraid.

When Ben’s friend Ernie Pyle, the famous Scripps-Howard columnist, arrived to cover the Blitz, Ben showed him how to navigate wartime London. “I feel like a mental child beside them,” Pyle wrote of his correspondent colleagues. “Yet I discovered that almost without exception they are friendly and helpful. And I discovered that among them almost nobody stands higher than my one old friend in London, Ben Robertson of PM.”

When Ben’s friend Ernie Pyle, the famous Scripps-Howard columnist, arrived to cover the Blitz, Ben showed him how to navigate wartime London. “I feel like a mental child beside them,” Pyle wrote of his correspondent colleagues. “Yet I discovered that almost without exception they are friendly and helpful. And I discovered that among them almost nobody stands higher than my one old friend in London, Ben Robertson of PM.”

Reporting for PM and the Chicago Sun, Robertson circled the globe often flying as a passenger on Pan American Airways’ famous Clipper flying boats and covering stories in the Pacific, Asia, and North Africa. He navigated the fine line between propaganda and advocacy journalism, certain that the United States should support Great Britain in its battle against Nazi Germany.

Robertson’s best-known—and last book—was published in 1942. “By the grace of God, my kinfolks and I are Carolinians…” opens Red Hills and Cotton: An Upcountry Memory. The book was widely-praised for the charm, warmth, and beauty of Robertson’s descriptions of his family and an energetic, self-confident South. Though noted for his writing about family and his ability to befriend the low-born as well as the noble, Ben never married. He did maintain a relationship with a woman friend, Jeanne Gadsden, who typed and edited his books and with whom he shared the foster parenting of a boy Ben brought home from the devastation of London’s Blitz. The boy, Leslie Phillips, would eventually become an American citizen and make a career in the US Air Force.

In January 1943, Ben joined first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and former Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie on a speaking tour to promote a campaign for Russian relief. Then, having accepted a job as head of the New York Herald Tribune’s London bureau, Robertson was on the move again.

On the morning of February 21, Robertson boarded the Yankee Clipper, one of Pan American’s flying boats, at the Marine Air  Terminal at New York’s Municipal Airport. Technically under the control of the Army, the Clippers though still crewed and piloted by Pan Am employees, were reserved for official government travel. Ben had waited for several days for his turn to board the big aircraft for its flight to Europe. Bound for Lisbon in neutral Portugal, Ben’s flight stopped first in Bermuda and then in the Azores before completing its journey on Lisbon’s Tagus River. The Clipper was a luxurious aircraft which had inaugurated trans-Atlantic passenger service. It was noted for aerial elegance, from its dining room to its sleeping berths. Settling into his seat, Ben looked across the narrow aisle to discover that his neighbor was Jane Froman, the prominent singer and a friend of Ben’s from their days together at the University of Missouri. Froman was bound for Europe with a USO troupe scheduled to perform for American military personnel.

Terminal at New York’s Municipal Airport. Technically under the control of the Army, the Clippers though still crewed and piloted by Pan Am employees, were reserved for official government travel. Ben had waited for several days for his turn to board the big aircraft for its flight to Europe. Bound for Lisbon in neutral Portugal, Ben’s flight stopped first in Bermuda and then in the Azores before completing its journey on Lisbon’s Tagus River. The Clipper was a luxurious aircraft which had inaugurated trans-Atlantic passenger service. It was noted for aerial elegance, from its dining room to its sleeping berths. Settling into his seat, Ben looked across the narrow aisle to discover that his neighbor was Jane Froman, the prominent singer and a friend of Ben’s from their days together at the University of Missouri. Froman was bound for Europe with a USO troupe scheduled to perform for American military personnel.

On February 22, after its seven-hour leg from Horta in the Azores, the Clipper descended toward Lisbon and approached the landing area on the Tagus River as a thunderstorm swept into the area. Although there was little wind or rain at the moment, lightning was reported nearby. Port officials noted that the Clipper, under the command of experienced captain R. O. D. Sullivan, was in radio contact as it neared its landing and that the flight was proceeding normally. Suddenly, as the aircraft turned left, its wing struck the water, flipping the Clipper and slamming it into the river at one hundred thirty miles per hour. Fifteen aboard, including Captain Sullivan and Jane Froman, survived the crash. Ben Robertson and twenty-three others were killed.

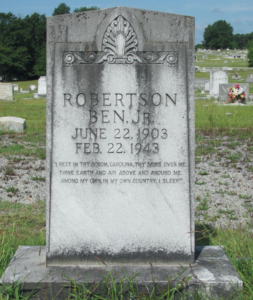

Robertson’s body was recovered about three weeks later some thirty miles downstream. It was returned by ship to the United States and then to Clemson where a funeral service was held on April 17. He was laid to rest in the family plot at Westview Cemetery in Liberty. College officials added Robertson to the Clemson Scroll of Honor by virtue of his status as an accredited war correspondent.

The SS Ben Robertson, a Liberty ship, was launched from Savannah, Georgia in January 1944 and served both the Normandy landings and operations in the Pacific. It is a fitting honor to a man who traveled on and over the seas, but perhaps the most poignant tribute was paid by his friend Murrow. On one of his broadcasts to America, Murrow described Robertson as “the least hard-boiled newspaperman I have ever known. He didn’t need to be, for his roots were deep in the red soil of Carolina, and he had a faith that is denied to many of us.” Murrow’s deep, familiar voice crackled over the airwaves, “There never was a night so black Ben couldn’t see the stars.”

The SS Ben Robertson, a Liberty ship, was launched from Savannah, Georgia in January 1944 and served both the Normandy landings and operations in the Pacific. It is a fitting honor to a man who traveled on and over the seas, but perhaps the most poignant tribute was paid by his friend Murrow. On one of his broadcasts to America, Murrow described Robertson as “the least hard-boiled newspaperman I have ever known. He didn’t need to be, for his roots were deep in the red soil of Carolina, and he had a faith that is denied to many of us.” Murrow’s deep, familiar voice crackled over the airwaves, “There never was a night so black Ben couldn’t see the stars.”

For more information on Benjamin Franklin Robertson, Jr. see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/benjamin-franklin-robertson/

For additional information on Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/

See also Jodie Peeler’s excellent biography, Ben Robertson: South Carolina Journalist and Author, University of South Carolina Press, 2019.