Scroll of Honor – William Robins English

In Japanese Captivity

The treatment of prisoners of war during World War II varied greatly depending upon the combatants involved. For Americans,  being captured by the Germans was preferable to being a prisoner of the Japanese—but then no one really got to choose.

being captured by the Germans was preferable to being a prisoner of the Japanese—but then no one really got to choose.

William Robins English of Columbia achieved an admirable record during his four years as a Clemson cadet. He was among the best drilled cadets of his Class of 1937, being selected to the Freshman, Sophomore, Junior and Senior Platoons. He served as a battalion sergeant major as a junior and as a cadet captain and battalion executive officer as a senior. In addition to military aptitude, English was recognized for leadership ability, being elected president of the Tiger Brotherhood. He served on the Central Dance Association, the Junior Ring Committee, and as a commencement marshal.

Following his graduation with a degree in general science, English returned to Columbia where he took a position with General Motors Acceptance Corporation. A reserve officer, English was called to active duty at Fort Jackson in December 1940 as the United States belatedly prepared for war. He was assigned to the 34th Infantry Regiment of the 8th Infantry Division. In October 1941, he married Martha Smith of Spartanburg. A month later, he was on a ship heading to the Philippines.

The Philippines had a reputation as an island paradise, with sunny days and cool nights, a place where military duty and social events mixed in a pleasant, predictable routine–until December 8, 1941 when the Japanese attacked.

Not long thereafter, English, now a captain, found himself in command of Filipino troops of the 81st Infantry Division defending the island of Cebu, which included the Philippines’ second largest municipality, Cebu City. US and Filipino forces under General MacArthur’s United States Army Forces in the Far East fought the Japanese tenaciously, holding out as long as possible without resupply and reinforcement. With the fall of Corregidor in May 1942, the 81st Division finally surrendered. A new ordeal was about to begin.

Back in Columbia, Martha had received regular letters from her husband since his deployment. Following a letter from Captain English in April, no further word arrived until the War Department notified her that her husband was missing in action. It would take another whole year for news of his capture by the Japanese to filter back to Martha through the Red Cross.

In the meantime, English would be imprisoned first on the island of Mindanao and then transferred to the infamous Camp #1 at Cabanatuan, Luzon. Following the October 1944 American landings at Leyte Gulf where MacArthur proclaimed his return to the Philippines, the Japanese began the cruel and often deadly process of transporting their prisoners of war to the Japanese home islands.

In December, English was loaded into the hold of a Japanese merchant ship along with other American prisoners. The conditions aboard these vessels reflected the names the Americans gave them: Hell Ships. Prisoners were left to the mercy of the elements, with no provision made for extra clothing for warmth, for food, water or medicines to treat the already malnourished and ill. In addition to the hunger, thirst, disease and increasingly cold weather as the ship headed north toward Japan, the prisoners were also at risk from their own countrymen.

Part of the American strategy of reducing Japan’s ability to continue the war was to gradually tighten the sea blockade by destroying enemy shipping. Unfortunately, that included the sinking of Japanese merchant ships that were sometimes—without the knowledge of US commanders—carrying American and Allied prisoners of war.

On December 15, 1944, the ship carrying English was torpedoed by a US submarine and sunk.  He was killed along with an unknown number of other Americans.

He was killed along with an unknown number of other Americans.

Japanese treatment toward prisoners of all nationalities was animated by racism and a sense that surrender was dishonorable. Americans captured by the Japanese during World War II died at a rate of thirty-three percent, compared to less than one and a half percent for Americans imprisoned by the Germans.

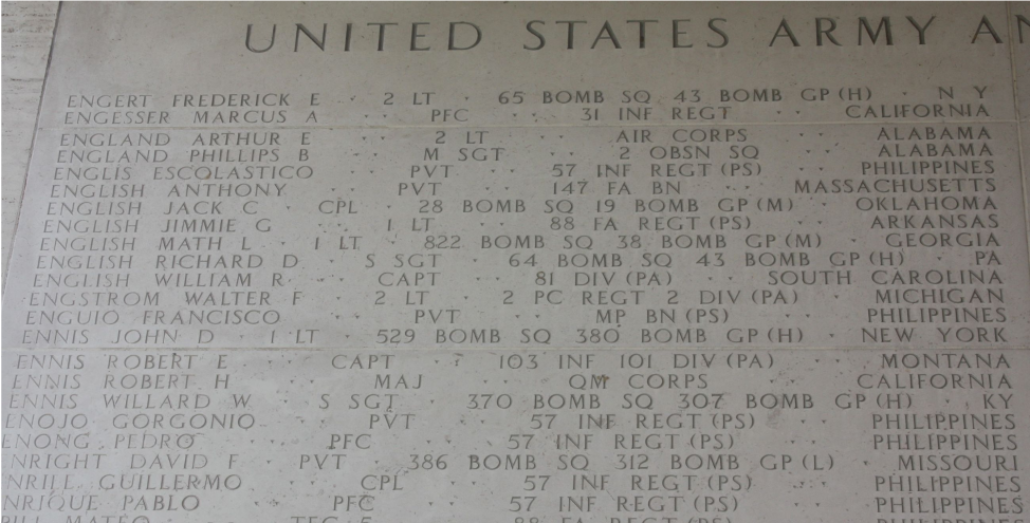

William Robins English was survived by his wife Martha, his mother, two sisters and a brother. He is memorialized at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.

For more information about William Robins English see:

https://soh.alumni.clemson.edu/scroll/william-robins-english/

For additional information about Clemson University’s Scroll of Honor visit: